| Back to Home |

Back to Local Interest |

|

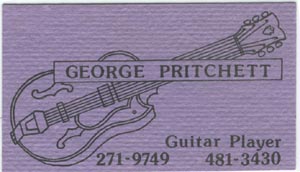

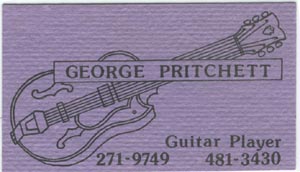

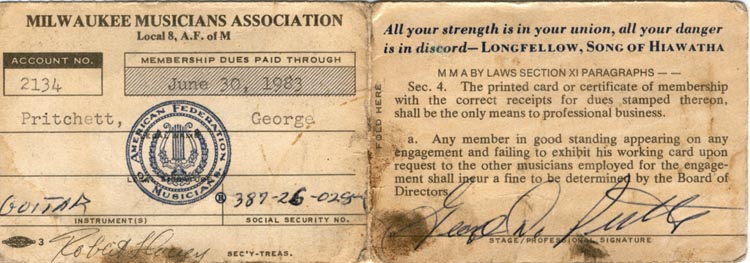

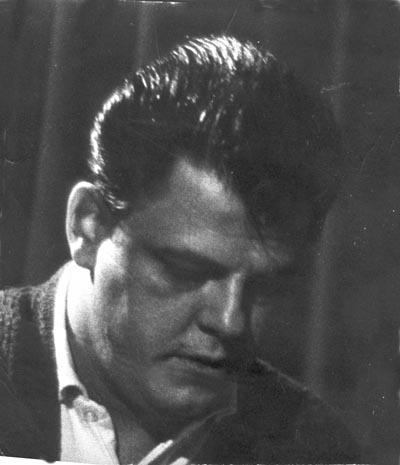

Jazzman

George Pritchett, and the life of a jazz musician

in Milwaukee

March 11, 1931 -Aug 24 1987 |

|

This is a story about how easy

it is for a determined, intelligent, and feeling person to simply lose control

over his life, and to lose track of what it is that he really wants. Like

much of the music they wrote and played, the lives of many of

the greater and lesser jazz performers seemed to be doomed to

an inevitable, and sometimes self destructive, melancholy. What

inspired me to write about the life of my father, George, was watching

the Ken Burns series "Jazz in America". It was a compilation of

great music, and brilliant talent, combined with the tragedy of short,

unhappy, and ruined lives. It seemed that the dedication, and relentless

pursuit of craft, which had given these people to great accomplishment,

had also chained them to failed lives. Watching this epic story of

pathos, it occurred to me that my own father's life was no different.

Indeed, I could readily recognize a familiar pattern in the lives of

all of the gifted, but often deeply flawed individuals who created and

defined this part of our culture. With a very few exceptions, all of

these people ended up in self destructive cycles which landed them

in prison, mental institutions, or hospitals. In a huge percentage

of cases, drug addiction, afflicted, and then shortened their lives.

They often couldn't retain friendships, and were never able to maintain

good family relationships. Most of these talented people were isolated,

even as they were surrounded by fans, and admirers. Indeed, many of

them had nothing in common with their many fans, and would have been

ignored, and outcast by these very people, if it were not for their

talents.

This is a story about how easy

it is for a determined, intelligent, and feeling person to simply lose control

over his life, and to lose track of what it is that he really wants. Like

much of the music they wrote and played, the lives of many of

the greater and lesser jazz performers seemed to be doomed to

an inevitable, and sometimes self destructive, melancholy. What

inspired me to write about the life of my father, George, was watching

the Ken Burns series "Jazz in America". It was a compilation of

great music, and brilliant talent, combined with the tragedy of short,

unhappy, and ruined lives. It seemed that the dedication, and relentless

pursuit of craft, which had given these people to great accomplishment,

had also chained them to failed lives. Watching this epic story of

pathos, it occurred to me that my own father's life was no different.

Indeed, I could readily recognize a familiar pattern in the lives of

all of the gifted, but often deeply flawed individuals who created and

defined this part of our culture. With a very few exceptions, all of

these people ended up in self destructive cycles which landed them

in prison, mental institutions, or hospitals. In a huge percentage

of cases, drug addiction, afflicted, and then shortened their lives.

They often couldn't retain friendships, and were never able to maintain

good family relationships. Most of these talented people were isolated,

even as they were surrounded by fans, and admirers. Indeed, many of

them had nothing in common with their many fans, and would have been

ignored, and outcast by these very people, if it were not for their

talents.Like many entertainers, George Pritchett brought a joy to his performances, that he could never quite seem to bring to his own life. Much of this was probably due to the hedonism which afflicts many performers, who seek and find much pleasure, but little happiness in life. It may also be due to the all consuming need for affirmation, and the need to be loved. There seems to be a constant evaluation process going on, by which the affections of friends and family must always be put to the test. Ego, too, plays it's part. Many of these people lean on their talent, or hide behind it. They must be the best at whatever it is that they do, because of a relentless self doubt. I think that, for most talented people, there is always a deep fear that they are only loved for their talent, and that without it, they would not be given a second thought. Sadly, there is a great deal of truth in this fear. So there is an ambiguous combination of dependency, and resentment over those who become their admirers and fans, and over the lives that their talent is able to give them. As a rule, these people tend to be very creative, intense, and driven, often volatile, and unpredictable. It is their gift, and their curse. |

||||

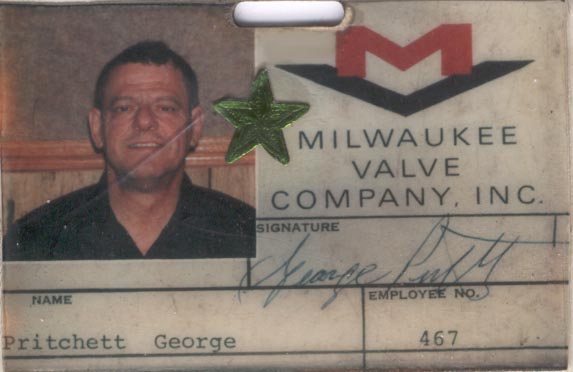

George Daniel Pritchett was

born on March 11, 1931, to a couple living on Milwaukee's near south

side. His father, Luther Cornelius (Neal) Pritchett, at 34 years

of age, was an alcoholic, who was often out of work. He had been

forced to leave his native state of Tennessee, after beating a man

so badly that he was said to have died. He was missing a big part

of one of his fingers, which it was said had been shot off. He was a

fairly good looking man, with a certain amount of charm, and was a very

snappy dresser. In Milwaukee, he met, and married Edna Giese, 31 when

George was born, a middle class German girl, from a reasonably good

family. This would turn out to be anything but a marriage made in heaven.

George Daniel Pritchett was

born on March 11, 1931, to a couple living on Milwaukee's near south

side. His father, Luther Cornelius (Neal) Pritchett, at 34 years

of age, was an alcoholic, who was often out of work. He had been

forced to leave his native state of Tennessee, after beating a man

so badly that he was said to have died. He was missing a big part

of one of his fingers, which it was said had been shot off. He was a

fairly good looking man, with a certain amount of charm, and was a very

snappy dresser. In Milwaukee, he met, and married Edna Giese, 31 when

George was born, a middle class German girl, from a reasonably good

family. This would turn out to be anything but a marriage made in heaven.Neal, George's father, besides being an alcoholic, was a womanizer, had a sharp temper, and little patience. He had been observed tipping the bed over one night to dump his wife out on the floor, when she refused to get up and make him breakfast, after he had been out all night drinking. By the time George was born, Neal was well advanced in his alcoholism, and had declined considerably, since his early youth. The family was, by this time, very poor, and very dysfunctional. George would be the second youngest boy, one more (Frank) would follow. He was born into a rather large family, with several big brothers, and sisters. George never spoke much about his father, or about his early life. What little we know about it came second hand from his brothers, and from his childhood friends. His silence on the matter speaks volumes, and speaks them loudly. By all accounts, his early life was just terrible. Though his mother had come into a small inheritance upon the death of her parents, it had been used by his father to buy a bar, which had gone out of business. The family was poor and didn't count for much, his father could not be depended upon, and his mother had lapsed into a hostile apathy. When George was struck by a car, as a young boy, neither parent could be found. His father was off somewhere, and it was latter discovered that his mother had been with a man. At various reunions, and family gatherings, I recall hearing stories about power being cut off, and men coming to repossess the furniture. I also heard stories about George's father being involved in numerous brawls, at his own bar, as well as at others, and of his being drunk much of the time. George spent much of his boyhood, sleeping on the floor in the kitchen. Back in those days, the part of the near south side, at 1424 S. 3rd, where the boys grew up was the Mexican neighborhood, with a slight influx of blacks. This is notable, because the America of the forties, and fifties, was far more segregated than the America of today. It was perfectly respectable, in those days, for a black or a Mexican to live in a black or Mexican neighborhood, but the same did not hold true for whites. If you were white, and lived in one of these neighborhoods, you were definitely looked down upon. The entire landscape was dismal, and left a definite mark on the children. All of the boys were habitually truant, and often in trouble. The older boys were sent to what was known at that time as Boy's Tech. Today it is called Milwaukee Technical High School, and only accepts the best students. Back in the days of my father's older brothers, this was far from the case. At that time, Boy's Tech was where recalcitrant unmanageable boys were sent as a sort of a last stop before reform school. It was thought that these boys would never be scholars, would probably not ever amount to much, and that the least the school system could do, before abandoning them completely, was to teach them a trade. The prescription was to keep the boys busy, under constant supervision, and to work them hard. The three brothers who attended, learned to be electricians, started their own contracting company, and did quite well for themselves. All three of these boys, my uncles, grew up to be millionaires. When George was a young man, his father died. He had gone to live for a time, with one of his brothers, but had moved back home. He graduated high school, and got work with his brothers, as an electrician's assistant. When George was a boy, his brother Emmit (Dick) had gotten a guitar, because he wanted to play country western music, like Gene Autry, and the other singing cowboys. George showed some interest, and after being shown a few things by Dick, spent several years teaching himself to play. It was not, however, cowboy music that George wanted to play. In the forties when George, and his friends were growing up, the cool, leading edge music was jazz. George, and his friends would spend hours sitting or laying, while listening to the music, and nodding their heads. George was a reasonably good guitar player, in his teens, and decided that he wanted to be a jazz man. Though there were many white swing bands, real jazz, was still thought of as black music, and the majority of real jazz men were black. There were exceptions, of course. Despite, or perhaps because of, the alcoholism rampant in his family, George did not start to drink until his mid to late  twenties. Old friends of his recall that, , as

a young man, he had an abiding contempt for what he called "drunken

assholes". Certainly he had seen enough of this in his father's

bar, and perhaps in his father himself. He would not touch the stuff.

Sadly, this was to change in latter years. One thing that young George

did do, however, was smoke pot, and take drugs. This became more common

in the late sixties, and seventies, but in the fifties it was still

pretty hard core, and serious. This did not help his reputation with

his brothers, and he was already starting to become an outcast within

his family. Though his brothers were hardly saints, none were involved

with drugs, and none had been arrested on any sort of felony charges.

twenties. Old friends of his recall that, , as

a young man, he had an abiding contempt for what he called "drunken

assholes". Certainly he had seen enough of this in his father's

bar, and perhaps in his father himself. He would not touch the stuff.

Sadly, this was to change in latter years. One thing that young George

did do, however, was smoke pot, and take drugs. This became more common

in the late sixties, and seventies, but in the fifties it was still

pretty hard core, and serious. This did not help his reputation with

his brothers, and he was already starting to become an outcast within

his family. Though his brothers were hardly saints, none were involved

with drugs, and none had been arrested on any sort of felony charges.As a very young man, George was convicted and sent to prison for a very short time, for breaking into a veterinarians office in an attempt to steal drugs. He had become a habitual drug user, and it seemed as if he was headed for the short, and dead end life of a junkie. To his credit, he cleaned things up, after being released, and was never in significant trouble again, until near the end of his life. Though he continued to smoke pot, he broke off his use of other drugs. In 1957, at the age of 26, he met and married Marlene Kannenberg, and meant to settle down, and have a family. It probably seemed to him, at the time, that he had found his way out of his old life, and that things were only going to get better. It would be a new life, but it would be a life filled with much of the baggage of the old. As with his own parents' marriage, this would turn out not to be a match made in heaven, and for similar reasons. For George, personal gratification, and latter on drinking, would take preference over everything. In addition, music, and his career would take precedence over family. There was also the deformed model of his own parents' failed marriage, which certainly made it's mark upon him. It may be that, looking back to his parents' marriage, he could not understand what he was doing wrong. He was said to have been a fairly quiet, and unassuming man, when he was young, but his dreams, indulgences, the club life, and the drinking would greatly change him. Had he worked in a factory, instead of pursuing a musical career, he would have received much less satisfaction, but perhaps would have been much happier. Who can say? |

||||

He actually met Billy Holiday once, not long before her death, when she was on her last legs. She had come to Milwaukee, to work a club. The club was full of whites who wanted to sit and drink with her, on her breaks. These were people who would not have wanted anything to do with her, had she not been famous. Certainly respectable white men did not sit in clubs, and drink with black women, not back in those days. She knew this, had seen it all before, and was suitably distant. George was in his mid twenties at the time, still slim and good looking. He walked up to her, this middle aged woman in poor health, and told her he thought she was beautiful. He didn't sit, didn't ask her to drink with him, and didn't seek an autograph. He said what he wanted to say, what he had probably wanted to say to her for years, and then left. If you have ever seen pictures of Billy Holiday, particularly in latter life, you know that she was anything but beautiful. Still, he was absolutely sincere; as far as he was concerned, she was beautiful. Having, he thought, absorbed the lessons of his father, and of the musicians he had always looked up to, George knew that he  would not allow himself to fall into that trap. He

was off the heavy drugs now, after all, and did not drink. His

life was cleaned up, and he was married with a child on the way.

He was hustling jobs, and was starting to get to the point where

it was looking as if he might actually be able to make a living with

his guitar. His life, it seemed, had taken a turn for the better. He

did, however, have a couple of serious flaws, which would plague him,

and anyone who tried to be close to him, all of his life. The first

was an all encompassing self indulgence, and impulsiveness. The second

was his bad temper, and a sporadic mean streak. He could be a very kind,

and amazingly generous person, who had a great deal of affection for the

people he valued, but he could turn suddenly, and unpredictably hostile

and mean, particularly when he was drinking, which was to become a bigger

and bigger part of his life.

would not allow himself to fall into that trap. He

was off the heavy drugs now, after all, and did not drink. His

life was cleaned up, and he was married with a child on the way.

He was hustling jobs, and was starting to get to the point where

it was looking as if he might actually be able to make a living with

his guitar. His life, it seemed, had taken a turn for the better. He

did, however, have a couple of serious flaws, which would plague him,

and anyone who tried to be close to him, all of his life. The first

was an all encompassing self indulgence, and impulsiveness. The second

was his bad temper, and a sporadic mean streak. He could be a very kind,

and amazingly generous person, who had a great deal of affection for the

people he valued, but he could turn suddenly, and unpredictably hostile

and mean, particularly when he was drinking, which was to become a bigger

and bigger part of his life.At some time, early in his career, George was approached by a man with an offer of permanent work, as a guitarist. The men that this man worked for owned a number of clubs, in various places, and were looking for talented musicians to sign. Of course, George would have to be signed exclusively with them, and he could only play where he was told. He would not be allowed any outside work. George said no, but the man insisted, and then told George who his bosses were. This was the local Mafia, which is a bit of a joke these days, but which was quite a powerful force, and taken very seriously back in the fifties. George still said no, and was shortly thereafter accosted one night, and had his fingers broken. Fortunately, there was no serious damage to the tendons, or he would probably never have been able to play again, but the damage to the bones was serious enough that he was out of work for a while. His fingers had to be set, but when they healed, he was able to play as well as before. The only reason that I know this story, is that I recall my dad taking me to a doctor, while in my teens, for an ingrown, and badly infected toe. I wanted to watch, and actually fainted, when the doctor incised, and then removed the nail, and allowed the toe to drain like a fountain. Dad happened to mention that I shouldn't feel bad, because he recalled having fainted when he was younger, and he had insisted on watching a doctor drill holes in his fingers to set them. He never gave any details, but I asked one of his long time friends about this, and he told me the story. He did not actually witness this event, but told me "George told those guys to go to Hell." Whether he actually said this or not, it would not have been out of character. As a certain amount of success and notoriety came George's way, the seeds of the most destructive force in his life began to be sown. "Hey, bartender. Get George a drink!" It was just that simple. Everyone drank in the clubs, everyone wanted to "catch the guys" up on the bandstand, and George knew that he had beaten that alcohol thing, and would never become a drunk like his father, so he drank. He also continued to smoke pot. Soon enough, he was drunk every night, and this had very unpleasant effects on his personality. He turned mean and abusive, most of this was directed towards his wife, though occasionally some would spill over to the children. Thinking back, I can not remember a single night of my childhood, or teens, when he did not come home drunk. There were two things that we learned very quickly. The first was that you could never really count on him, and the second was that you never knew how he was going to act. If George said that he was going to do something, or be somewhere, you knew that maybe he would, and maybe he wouldn't. After a while, people who knew him well, just came to accept this, with a shrug "Oh well, that's just George for you." For most of his life, the future was always a very uncertain place for George. He had thus learned to give it little thought, and always seemed to live for the present and little more.  There were also the women, which

his talent, looks as a young man, and position gave him access

to. Along with the drinking, George was unfaithful to his marriage

vows, almost from the beginning. This was a real tragedy, because

he had a genuine love and affection for his family, and desperately

wanted things to work out well; but for George, pleasure always took

first place before happiness. It may be that life had offered him little

happiness, or that he though it to be beyond him. Perhaps he couldn't even

conceive of what true happiness might be. Pleasure, on the other hand, he

understood quite well. To friends, enemies, and neutral observers alike,

he became "Crazy George", back as early as the late fifties.

There were also the women, which

his talent, looks as a young man, and position gave him access

to. Along with the drinking, George was unfaithful to his marriage

vows, almost from the beginning. This was a real tragedy, because

he had a genuine love and affection for his family, and desperately

wanted things to work out well; but for George, pleasure always took

first place before happiness. It may be that life had offered him little

happiness, or that he though it to be beyond him. Perhaps he couldn't even

conceive of what true happiness might be. Pleasure, on the other hand, he

understood quite well. To friends, enemies, and neutral observers alike,

he became "Crazy George", back as early as the late fifties. What really set him apart was his technical mastery of the instrument. He was fast, and he could chord the way others could play single notes. It was rare for him to play anything simply, and embellishment, and complexity accompanied his great speed during a performance. Many people who knew music, were shocked to see him playing in little bars, and clubs around town. "You should get out of Milwaukee, and go to New York, or Los Angeles." was a comment he often heard, or else "What are you doing here?" All though the sixties, people were telling him that he was too good to stay in Milwaukee, and that he should get out and go to a better market. People do not make musical careers here. This was a mantra that he had heard all of his life. Still, for whatever reason, he stayed. It may have been his family, or his brothers, perhaps it was insecurity or fear. It may also have been that he now knew so many people and was so well connected, that he didn't want to give the city up. It certainly was not for the love of Milwaukee. The Milwaukee of the fifties, and most of the sixties was a blue collar, middle class, fairly unsophisticated place. People here bowled, went on picnics, went to church festivals, and went down to the lake. This was what we did here. Oh there was one other thing; people here went out drinking. This was a big part of the life here. For decades, Milwaukee has had the highest per capita consumption of alcohol, second only to Las Vegas. Only a small part of this was connected with the club scene, however active it may have been decades ago. Most was centered around the little corner bar, which in some parts of town sat on three out of four corners on an intersection. This was a night life of sorts, but it was the bar scene of beer nuts, bowling, Slim Jims, pickled eggs, and pool tables. Milwaukee did have a number of clubs, and night spots, but the taste of the majority of city residents did not embrace them. Still, there was more than the club scene, and George worked with the Milwaukee Symphony, and was sometimes hired as part of show bands or orchestras at the Pabst, and other theaters. There was also the event circuit, weddings, awards ceremonies, and catered affairs. These were often one shot jobs with larger bands, and required a suit and tie. George's latter trademark attire would be a black knit shirt, and black pants. These were easy to clean, comfortable, and didn't make him look fat in his latter years, after he began to put on weight. During and after her wedding, my mom remembers being offered help, sympathy, and being given advice on how to handle George. This was from his friends, who couldn't imagine "Crazy George" settling down and becoming a family man. Still, it seems that had it not been for the drinking, he may have been able to pull things together, and make them work. Even with his faults, he was not generally a bad man, but alcohol turned him into something monstrous. If he was drunk, which was most nights, or hung over and cranky, which was most days, you wanted nothing to do with him. In his right mind, he was intelligent, kind, and fun to be with, but this happened more and more infrequently, as his drinking got worse. He worked all over town, and had developed quite a following by the time he reached his early thirties. He knew and was known by, everybody. There was little indecisiveness on the part of those who knew him; you either really liked George, or you really hated him. He worked all of the clubs, and seemed to have a line on everything. It reached a point where if you needed anything from auto repair to dental repair, George had a friend who could help you out. Everywhere he went, and whatever he needed, there was always someone who knew him, or had seen him play. In nearly every bar that he walked into, on or off the job, someone would recognize him. "George? Are you George Pritchett? Bartender, get George a drink." |

||||

|

Whatever talent George had,

and however much he might have hustled, this was Milwaukee, and

it was impossible to make a living here as a musician, particularly

as a jazz musician. People in Milwaukee wanted polkas at weddings,

rock bands at bars or discos, and big bands at business affairs. Even

had this not been the case, there were only so many clubs, and people

only went out on so many nights. This was not a resort, tourist, or

entertainment town, and there was no real full time work here for musicians. The jazz scene in America at that time was in a state of dormancy anyway. Veteran jazz players either went to Europe or Asia, played rock, or country, or did studio work. Those who couldn't or wouldn't, got day jobs, or went broke. As for the new jazz players, well, there didn't really seem to be any. Though a resurgence would come latter, at the time it seemed like jazz had outlived it's day, and would soon pass into history. One of the advantages of the intensity with which George pursued his craft, was that he immersed himself so completely that he knew guitars inside and out. He loved not just the music, but also the guitars through which it was made. He knew their history, what they were worth, how certain guitars played better than certain others, for certain types of musical styles, and even how a guitar should fit the individual's hand and style of playing. He knew when a given guitar line started, and stopped being a good line, or when it was changed over to a different factory, and how this affected playability. As a result he was constantly tinkering with his guitars, and trading them. He was thus, a natural as a guitar salesman, and as a consultant to other musicians. He taught and sold at a number of local music stores, most notably, the now defunct Academy of Music, on Milwaukee's near north side, and Crown Music, in Bay View. In these he kept his hand on the pulse of development, manufacturing, and pricing. He also met large numbers of musicians who were outside of the club life, and took on numerous students, several of whom became quite successful musicians in their own right. One of the Music stores he worked at was Zeb Billings. Zeb did more organ and piano than guitar sales, but George was a good musician, knew people, and could sell. He could also teach, and had some students while he was working for Zeb. While working for Zeb Billings, in the mid sixties, George did his first recording sessions. This was not a star maker, but rather a series of recordings for some instructional and accompaniment tapes that were being produced for piano and organ students. They were done at the local Dave Kenney studios. He took us down there one day, and we got to play in the sound booth, as well as out in the studio itself. It was interesting, but we really had no idea of what was going on, and half expected to hear dad on the radio or something. We were just kids. In retrospect, this must have been very tedious, and dull work, particularly for a musician with any kind of talent or style. But it did pay the bills. Though technically, George gave in and took a day job, this was still a job in the music business, and it may be that in teaching others he helped to sharpen his own skills even more. He soon began to take on only advanced guitarists, and you actually had to demonstrate to him that you were good enough, before he would accept you as a student. He would drop students who would not practice, or who did not work hard enough. He had little patience for those who did not take their music seriously. Actually, he had little patience in general, and had been known to yell at students who were slow to catch on. He rarely taught children, including his own. My brother and I both asked him for lessons, as young children. He sent us to another teacher, who handled children, telling us that when we got good enough, he would take over our instruction. We soon lost interest, though in latter years, my brother Jim took up guitar. I will not go into great details about family life; this is personal stuff; but it was very often, not good. This seems to be a common factor in the lives of many, if not most, jazz artists. George's early life with his  parents' family was like something out of a Dickens novel,

and certain dependence on his brothers, to make up for his own father's

lack of responsibility, forever colored his view of them, making him

think more of them than he perhaps should of. His brothers always remained

very important to him. He was never as important to them as they had

been to him. Though he had left behind a big family, his own father was

dead by the time of George's marriage.

parents' family was like something out of a Dickens novel,

and certain dependence on his brothers, to make up for his own father's

lack of responsibility, forever colored his view of them, making him

think more of them than he perhaps should of. His brothers always remained

very important to him. He was never as important to them as they had

been to him. Though he had left behind a big family, his own father was

dead by the time of George's marriage.As much as he valued their opinion, and friendship, George was always just outside of the family circle of his brothers. Most of his relatives went into the family electrical contracting business, worked in construction, or in a factory. They had "normal" jobs, normal lives, and were normal people. George was different, and most were not quite sure what to make of him. Guitar playing was not exactly work to most of them, at least not in the traditional sense, and it was considered somewhat of a fool's dream, to pursue such a thing as a career. He also spent most of his working hours in various bars, and clubs, and slept all day, while most people were working. So there was always a bit of disapproval, or at least doubt present. When George became successful, it seemed to come as a bit of a surprise to his brothers, and other relatives. Though they gladly made use of their bragging rights, there was still just a bit of a barrier up. George did have his own family, however.  If his work life, and the associated

life style, colored the attitudes of his brothers about him, it absolutely

destroyed his own family life. George's drinking, developing bad temper,

and womanizing did not make him an ideal husband or father. He also

did not make a regular income. The money came and went, as George was

able to find club work. There was little security, and always, there

seemed to be conflict, and instability. The couple divorced, after ten

years of marriage, though neither ever remarried. Though divorced, they

remained together for years, except for a few brief periods, and then the

final separation.

If his work life, and the associated

life style, colored the attitudes of his brothers about him, it absolutely

destroyed his own family life. George's drinking, developing bad temper,

and womanizing did not make him an ideal husband or father. He also

did not make a regular income. The money came and went, as George was

able to find club work. There was little security, and always, there

seemed to be conflict, and instability. The couple divorced, after ten

years of marriage, though neither ever remarried. Though divorced, they

remained together for years, except for a few brief periods, and then the

final separation. The family moved around quite a bit. Every year or two we all packed up, and started over in a new place. Though the place may have been new, we took our old lives with us. The family stayed on the south side of Milwaukee, until the early seventies, several years after the divorce, when the family broke up. George moved into the Shorecrest Hotel; the rest of the family moved into a small apartment on Prospect Avenue, in Milwaukee's east side. Though it was small, the place had a great view of the lake, and we had some interesting times there. George was doing quite well at this time, as he had made his albums, was in demand as a guitarist, and was finally living part of the life that he had always wanted; but he missed his family. George had some success now, and wanted to get back together. He was doing well, and missed everyone, and thought that now he might be able to be the man he wanted to be, and do things right. He made some promises, that he thought he would now be able to keep. His life long dreams were coming true, and he wanted his family back. After a year or so of separation, the couple got back together, and had another son, Christopher. The family got back together, in a much bigger apartment, still on Milwaukee's east side. These were probably the best few years of George's life,  possibly the only really good ones. He was back with his

family, he was a success, with a good steady income, and he had a

new son.. These were also the years of Pritchett's, when he was in business

with his brothers, and it finally seemed as if, they too, had accepted

him, and held him in high regard. Even so, there were problems, and after

a few years, and several more moves, the family split up again, never

to get back together, until a brief period just before George's death.

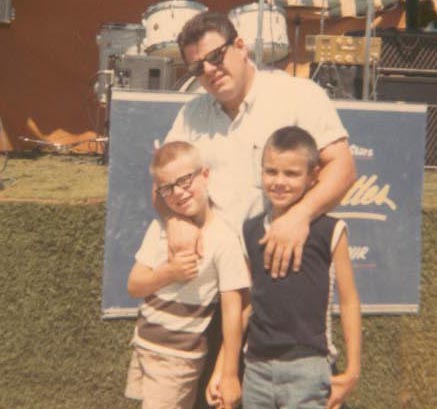

The photo to the right shows the family on an Easter Sunday, back in the

early sixties, when they had been married perhaps six years. One of the

things that strikes me about this photo, is that it was a holiday, and

we were all gathered together for a family holiday photograph, and yet no

one is smiling, not even the children. That pretty much sums up the early

family life.

possibly the only really good ones. He was back with his

family, he was a success, with a good steady income, and he had a

new son.. These were also the years of Pritchett's, when he was in business

with his brothers, and it finally seemed as if, they too, had accepted

him, and held him in high regard. Even so, there were problems, and after

a few years, and several more moves, the family split up again, never

to get back together, until a brief period just before George's death.

The photo to the right shows the family on an Easter Sunday, back in the

early sixties, when they had been married perhaps six years. One of the

things that strikes me about this photo, is that it was a holiday, and

we were all gathered together for a family holiday photograph, and yet no

one is smiling, not even the children. That pretty much sums up the early

family life. Things actually improved a bit after the divorce. It may have finally occurred to George that there were serious problems in the way that he was living, and that his parents' family life was not a good model to emulate. The family moved, and George seemed to calm down quite a bit. He also seemed to make an effort normalizing family life. I recall some trips to Door County, and to some other places, and an increase in socialization with his brothers, our uncles, and the rest of his relatives. Things were not perfect, and George slipped often, but he was trying. He wanted to keep his family. His initial success, with Buddy Rich, and then with his albums may have hurt these efforts a bit. Certainly spending a year away from home didn't help, but there was also the shift in emphasis that these breaks produced. Once things started to break  for him, he threw himself back in to his music. Many of

his old bad habits also began to resurface. It may have been a difficult

adjustment to move from being a local talent scuffling for jobs, to

being in demand and receiving adulation, and high regard from a previously

unconcerned public and press. George would hardly be the first person

to have had his head turned by such attention, particularly after years

of indifference.

for him, he threw himself back in to his music. Many of

his old bad habits also began to resurface. It may have been a difficult

adjustment to move from being a local talent scuffling for jobs, to

being in demand and receiving adulation, and high regard from a previously

unconcerned public and press. George would hardly be the first person

to have had his head turned by such attention, particularly after years

of indifference.Still, with all of his faults, he was a loving man, and it is a great tragedy that he could rarely keep himself in check. A more normal life, and a more conventional career might have given him, or forced him to develop, these abilities, but his past, and the atmosphere of the club life, gave him no incentive, and few examples from which to develop such traits. It even encouraged many of these behaviors, making them seem like distinguishing personal traits or a noble trueness to ones self. This would be hard on everyone, but hardest on George himself. On his death bed, he spent a great deal of time apologizing, and expressing regret. There was no need; it was too late. After the final break up, George went to live in a tiny one room apartment above the Oriental Pharmacy, on Milwaukee's east side. The rest of the family lived a mile or so up the road, by the university. George visited often, and doted on his youngest son, somewhat, but the couple had no no plans to get back together, and the two got along fairly well as friends. He was also beginning to get along much better with his two older sons. In particular the middle son, Jim, improved his relationship with his father, even to the extent that George helped him to improve his guitar playing. There had been considerable conflict with his sons, particularly with the oldest, in years gone by. This was in part, the normal conflict that exists when children reach the age, at which they are able to see their parents as people, rather than as parents. In George's case, however, there were some added complications. His bad habits, alcoholism, and past mistakes, fanned the flames of the normal adolescent revolt, and gave considerable ammunition, to be used in the ensuing conflicts. Much of this was likely very distressing to George, not the least because so much was justifiable. During these years, I was unrelentingly hostile, while Jim would take off, from time to time, and hitch hike across the country, letting his hair grow long, and embracing the rock culture. As George entered his fifties, much of this conflict went away or was forgotten. He also got along very well with his youngest When things got really bad, and George's health became chronically impaired, the family took two apartments in the same building where George lived. Other factors played a part, but it was thought that it would be a good idea to move in to be close to him, as his health was failing. This was particularly true for his youngest son, for whom it was thought that the loss of his father was imminent. Though living above the Oriental was not paradise, there was something kind of secure, and reassuring, with everyone living in the same building. Certainly George was happy to have his family close, if not reestablished. He was in the middle of Milwaukee's east side, where much of the work was, and he was in the same building that had once housed Pritchett's. Nearly everyone in the building knew him, and many were his friends, some having been so for years. The family lived on the third floor, in two adjacent apartments. The youngest son lived with his mother, while the two older sons, now grown, lived next door. George lived one floor down, and it was a simple matter for him to visit, or be visited. His ex wife worked right downstairs, in the Oriental Pharmacy, and both sons worked within a few blocks of the building. No one went very far, during this time. In a pattern not entirely different from that of George's own childhood and early family life, Chris had depended somewhat on  his brothers to take up the slack. This would become more

the case every year, particularly after George's health became seriously

impaired, and would be complete after his death, when Chris was twelve.

There was quite a difference in age between the first two brothers and

Chris. They were really almost a generation apart. Chris was born just

before the sixteenth birthday of his oldest brother, when the middle

brother was fourteen. This was during the best part of George's life,

when he was successful, had his club, and had made up with his family.

For a very short time, George was probably pretty happy, though like most

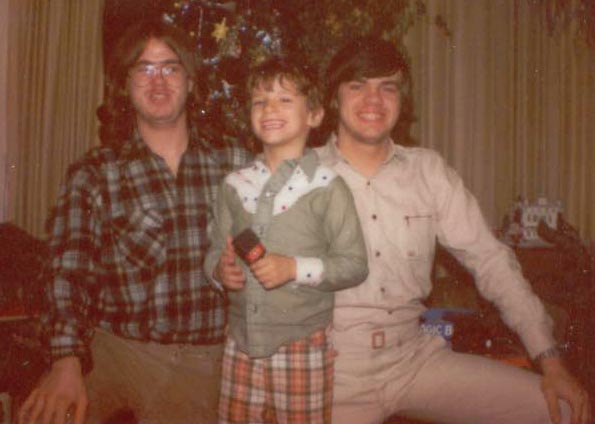

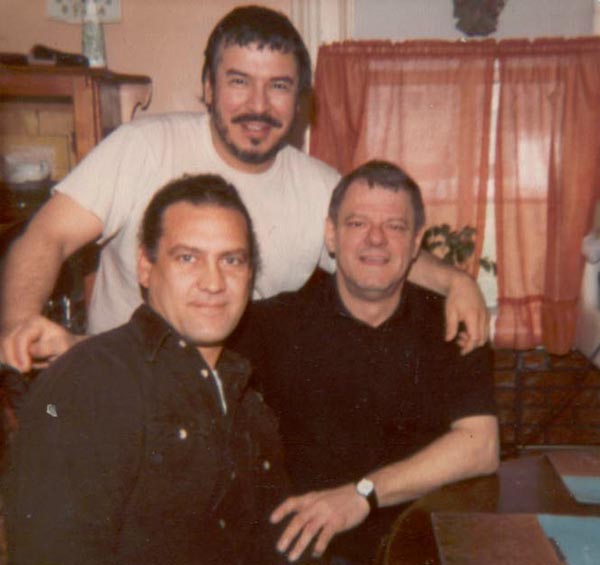

good things in his life, it would not last for long. In the picture shown

to the left, Chris, in the center of the photo, was probably three, which

would make his brother Jim (left) about eighteen, and me (right) about nineteen.

Less than a year after this photo was taken, Jim was shot, and had his right

arm permanently impaired. Though he can still play guitar, and get much

use from the arm, it is unable to straighten out, and he can not put a

great deal of weight on it. He is also no longer able to play the drums.

his brothers to take up the slack. This would become more

the case every year, particularly after George's health became seriously

impaired, and would be complete after his death, when Chris was twelve.

There was quite a difference in age between the first two brothers and

Chris. They were really almost a generation apart. Chris was born just

before the sixteenth birthday of his oldest brother, when the middle

brother was fourteen. This was during the best part of George's life,

when he was successful, had his club, and had made up with his family.

For a very short time, George was probably pretty happy, though like most

good things in his life, it would not last for long. In the picture shown

to the left, Chris, in the center of the photo, was probably three, which

would make his brother Jim (left) about eighteen, and me (right) about nineteen.

Less than a year after this photo was taken, Jim was shot, and had his right

arm permanently impaired. Though he can still play guitar, and get much

use from the arm, it is unable to straighten out, and he can not put a

great deal of weight on it. He is also no longer able to play the drums. |

||||

|

Sometime in 1970,

George was playing a club job, when some visitors to Milwaukee

came to hear him play. Among them was Buddy Rich, the premier drummer,

and big band leader. Since the late thirties, Buddy Rich had been considered

to be the finest jazz drummer in the world. He had been told that

there was this local guitarist that he just had to hear. He immediately

approached George, introduced himself, and offered George a job with

his band. This came out of the blue, and George was stunned. He asked

for some time, as he wanted to discuss the matter with his family, and

think things over. This was a big move, after all. Buddy Rich agreed.

The Buddy Rich band was one of the last of the original big bands, and one of the only real jazz bands left in the country. This was the big time. Buddy Rich had known and performed with all of the greats, and was one of the greats himself. He had been on Johnny Carson's Tonight Show on numerous occasions, back when the Tonight Show was the last word in night time  television. He had performed and toured with Sinatra, with

Louis Armstrong, with Ella, and Dizzy. In the old days, he had been

with Arte Shaw, and Tommy Dorsey. He had also performed with George's

favorites, Billy Holiday, and Charlie Parker. In short, he had performed

with everybody. Buddy Rich had been in the center of the jazz world,

almost as long as there had been a jazz world. He was one of the few

giants left in jazz, and he wanted George.

television. He had performed and toured with Sinatra, with

Louis Armstrong, with Ella, and Dizzy. In the old days, he had been

with Arte Shaw, and Tommy Dorsey. He had also performed with George's

favorites, Billy Holiday, and Charlie Parker. In short, he had performed

with everybody. Buddy Rich had been in the center of the jazz world,

almost as long as there had been a jazz world. He was one of the few

giants left in jazz, and he wanted George.There was little doubt as to what answer George was to give Buddy. The family discussion centered around what to do with the car, how we would have to manage on a bit less, since dad would need living expenses on the road, and on how we would need to give mom a break, since she would be here on her own. In 1970, dad went on the road with the Buddy Rich band. This was a career break, and an opportunity to work with excellent musicians, but the road was neither glamorous, nor fun. Buddy Rich, talented as he was, could be a tyrant, and throw tantrums. Dad stayed with him for a year. The band traveled, and essentially lived, on a big bus. They toured, charging $5000 per appearance. This was a fairly hefty sum, in 1970, but it had to cover salaries, operating expenses, management fees, and Buddie's own cut. George was his highest paid musician, while he was with the band. George needed the extra money because, unlike most of the other band members, he was married and had children. Much of the expense of being and working on the road, was borne by the band members themselves. In addition to this, George had a family to support. In Buddy Rich, George actually found someone of his own temperament, who took the craft as seriously as he did himself. Actually, the whole band was composed of very serious musicians, who had trained themselves to be the best. Even so, Buddy Rich was an obsessive perfectionist, who threw himself entirely into what he did, and had no patience for anyone who did not. |

||||

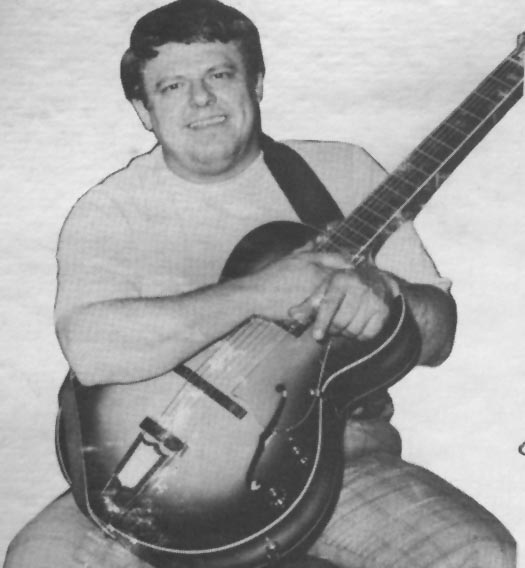

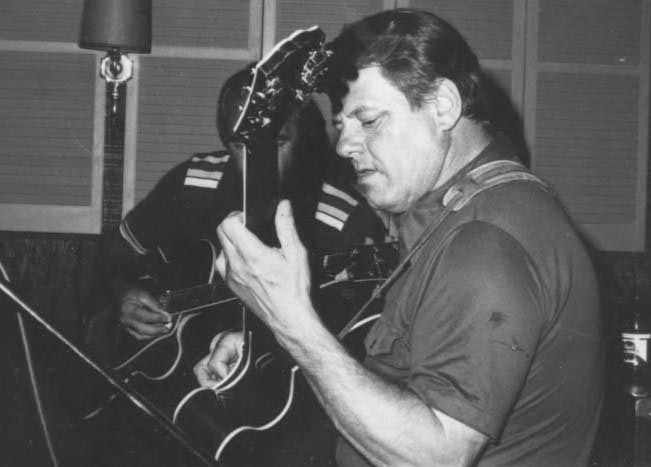

His short tour with the Buddy

Rich Band exposed his showmanship style, and amazing mastery

of the instrument, to jazz fans all over the country. A reviewer

from Downbeat magazine heard him, and called him one of the best

guitarists in the country. On a technical level, regarding brilliance,

speed, and physical ability, he was probably without equal in the

world, though he did not always have the melodic refinement of some of

the giants of the jazz world. People were particularly amazed at his

speed. He could play chords in sixteenth time and faster, that is, sixteen

chords a second. Nobody played like this. This did not escape the notice

of certain people, particularly at the local level, who saw some potential

in this dexterous jazz man. He was soon contacted by Pete Stocke, who

ran a local electronics distribution company, called Taylor Electric.

He had some connections with the huge RCA conglomerate, and wanted to

produce a record album, featuring George. The recording was made in

studio A, at the RCA Mid-America Recording Center, in Chicago, on June

24th, 1971. George went down the day before, and stayed in Chicago,

so that he would not be late for the morning session.

His short tour with the Buddy

Rich Band exposed his showmanship style, and amazing mastery

of the instrument, to jazz fans all over the country. A reviewer

from Downbeat magazine heard him, and called him one of the best

guitarists in the country. On a technical level, regarding brilliance,

speed, and physical ability, he was probably without equal in the

world, though he did not always have the melodic refinement of some of

the giants of the jazz world. People were particularly amazed at his

speed. He could play chords in sixteenth time and faster, that is, sixteen

chords a second. Nobody played like this. This did not escape the notice

of certain people, particularly at the local level, who saw some potential

in this dexterous jazz man. He was soon contacted by Pete Stocke, who

ran a local electronics distribution company, called Taylor Electric.

He had some connections with the huge RCA conglomerate, and wanted to

produce a record album, featuring George. The recording was made in

studio A, at the RCA Mid-America Recording Center, in Chicago, on June

24th, 1971. George went down the day before, and stayed in Chicago,

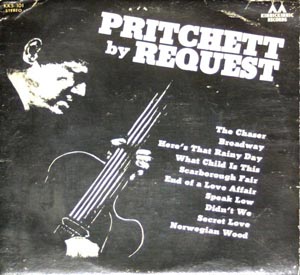

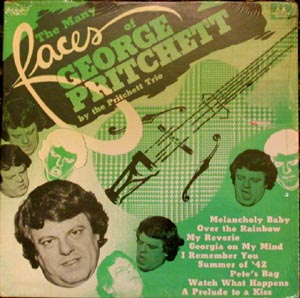

so that he would not be late for the morning session.The first album was called Pritchett by Request, and did well enough, that in 1973 George was invited to do a second, called The Many Faces of George Pritchett. This second album also did pretty well, despite having the ugliest, worst designed cover I have ever seen on any album. If you are wondering why you have never heard of George, and why you may not have ever seen these albums, it is for two reasons. The first is, that this was a long time ago, over thirty years. The second, is that these were recorded on a small local label, Kinnickinnic records. As far as I know, these are the only two albums recorded on this label. The were catalog numbers 0-KINN-101, and 0-KINN-102. These records had local, as well as limited national distribution. Still, the albums did quite well, George did make some money off of them, and was now a recorded musician, which got him taken a bit more seriously. It seemed that the talent he had developed, all of the years of hustling, his travel with Buddy Rich, and the decision to become a full time musician were finally going to pay off. He was given jobs playing at Milwaukee's famous Summerfest music festival, as well as offers for resort work, and even an invitation to a jazz festival in France. His albums were now all the resume' he needed. He worked the Summerfest jobs, but never followed up on the resort work, or the festival offers. It may be that his experiences on the road with the Buddy Rich band made him averse to travel. He was also quite happy to be the leading figure in the Milwaukee music scene. One day George was contacted by Pete Stocke, the man who had produced his albums for Kinnickinnic Records, and asked if he wanted to do a recording for the RCA label. He jumped at the chance. Here was the big time, national distribution on a major label. RCA executives had heard his records, and wanted to take him on. This was to be a first class effort all the way. They were certain that they had a major talent here, and wanted to promote their new artist. Jazz was beginning to stir, from it's long sleep, and seemed to be increasing in popularity. Though rock and roll still dominated the scene, jazz was redeveloping an intense following, and was beginning to reassert it's influence over rock, and pop music. It was also getting a reputation as the sophisticated and thinking persons music. You now listened to jazz to show your maturity and good taste. Jazz had also become, once again, the cool music. Many of the old jazz men, who for years had been playing country, rock, or studio music to earn a living, now began to play jazz again. Though the wheel had just started to turn, and jazz had not yet come to the top, record industry executives could see the writing on the wall, and wanted to begin to assemble a stable of jazz artists, in anticipation of the coming trend. George was to become one of the newly discovered, and promoted artists. As part of the new full blown treatment, George would be recorded at a first class studio, for RCA records, rather than at the  local Dave Kenny Studio, where he had started out.

There was no first class studio here at the time, but one did

exist in Lake Geneva, about a one hour drive from Milwaukee. This

beat having to go and stay in a room down in Chicago, and a session

was scheduled. In addition to the first class studio, the album was

to be handed over to an experienced promotion team, with good artists,

and seasoned promotional writers. It was also to be nationally distributed,

advertised, and treated as a work by a major artist. George had gotten

the break that he had worked so long and hard to get. This was a ticket

to the big time.

local Dave Kenny Studio, where he had started out.

There was no first class studio here at the time, but one did

exist in Lake Geneva, about a one hour drive from Milwaukee. This

beat having to go and stay in a room down in Chicago, and a session

was scheduled. In addition to the first class studio, the album was

to be handed over to an experienced promotion team, with good artists,

and seasoned promotional writers. It was also to be nationally distributed,

advertised, and treated as a work by a major artist. George had gotten

the break that he had worked so long and hard to get. This was a ticket

to the big time.The recording session was scheduled for the morning, and George over slept. I actually remember that day, and remember him being very nervous about it. He called and apologized, and the session was rescheduled. This was an expensive thing for the studio. Recording engineers, and other staff members had to be scheduled for the session, and RCA had to pay a fee for the use of the studio itself. Back in those days, it cost a fortune to build a studio, and studio time did not come cheap. George over slept for the second session. I know he called again, and I do not recall if a third session was scheduled or not. What I do know is that the project was dropped, and George never was to put a record out on the RCA label. In all fairness to George, this isn't as irresponsible as it sounds. Keep in mind that he was working days, teaching guitar, and selling, and was also working nights at various clubs. He had a family, with two teen aged sons, and was having considerable domestic problems. His continual drinking, too, took a toll on him, now in his early forties, so that he was always exhausted. He may also have feared that if he were to go in tired and beat, his performance might not be up to par. Still, after all of the years of work, to have made it to the gates of heaven, and then to have dropped the key, must have been worse than anything imaginable. I can't imagine what was going through his mind, probably for years, possibly for the rest of his life, over this matter. The saddest things in life are those that might have been. |

||||

|

The loss of the RCA album was

a huge blow for George, but he was nothing if not resilient. He

had been hustling all of his life. His work with Buddy Rich, along

with his two albums, had made George a pretty big local celebrity,

so work was now much easier to find. Though life on the road had driven

him nuts, it was difficult, after touring with a world famous band, to

settle for a life of hustling club jobs again. Fortunately, a solution

quickly presented itself. Three of George's brothers had recently gone

in together, and bought the Oriental Building. This was an elaborate

multi function building complex built in the twenties. It housed the Oriental

Theater, a series of store fronts, and offices, the Oriental Pharmacy,

and a block of apartments. It also included a bowling alley and bar,

as well as significant unused space. This was all located on one of the

busiest intersections in town. This was the heart of Milwaukee's East

Side, halfway between Downtown, and the University. The brothers decided that this would be a chance to get into the big time. George was famous locally, was known nationally, yet he was once more destined to be hustling club jobs; and they had all of this room just sitting there. Why not make it over into a club, and feature George as the resident musician? The dozen or so lanes were torn out, and the floor was filled in and leveled with concrete. This produced a large rectangular room, which looked like a low ceilinged basketball court. The room was huge. Think about how big a bowling alley is, and you get the idea. Because the lanes had to be filled in, the whole room sat a foot or two above the level of the rest of the floor, so steps were put in, along with an entranceway. The room seemed to fall together, in fits and starts. A pair of glass doors were retrieved from an office building, which was being torn down, a huge wooden slab of a door was salvaged from somewhere, and refinished into a thing of beauty, by dad's friend Louie Kane. Other friends, found other items. A local restaurant, located at the Performing Arts Center (now the Marcus Center), was remodeling. The name of the place was The Velvet Chair, and it had scores of green tufted velvet chairs that it was selling off at bargain prices. A huge, used stainless bar was found, and installed. The bar rails, and stools were refinished in green to match the chairs. Green carpeting was laid down, and the walls were finished to half of their height in paneling, with matching carpeting going up the rest of the way to the newly installed suspended ceiling. A small stage was built about halfway along the wall opposite the bar, with a gold curtain set behind it, and a dance floor was laid at the far end of the room. A huge blown up photo was mounted in the wall behind the bar, of the Buddy Rich band, with George sitting in the front row. The end result was a huge, rectangular, green room, bigger than most of the ball rooms in town, but with a rather low ceiling Pritchett's actually had a very special place in Milwaukee's cultural and night life, for a time. Everyone showed up here. Local politicians, celebrities, entertainers, and money people all made this their spot. This was the premier place to go and hear music played by Milwaukee's own star, to meet friends, to hang out, or to be seen. If you wanted to impress someone from out of town, you took them to George's place. If you were visiting, and wanted to know where the hot spot was, you were told to go to George's. If anyone famous was in town, from baseball players, to actors, to musicians, they would inevitably show up at Pritchett's. Far from being a refined and upper crust place, Pritchett's also attracted a huge crowd of jazz enthusiasts from Milwaukee's inner city, along with the local college crowd, and people from the neighborhood. It also attracted most of what was left of the old guard of the club life, from the fifties, and sixties. While it lasted, it was a great time and place to be George. This little piece of paradise actually lasted for several years; but nothing good ever seems to last forever. Business did eventually decline, for a number of reasons. For one thing, no hot spot can operate at such a pitch for very long, without burning itself out. Things become passé', and eventually people start to look for the next trendy place, or the newest hot spot; you know, the place that no one knows about yet. Milwaukee was also a limited market. There were only so many people here, only so many of them were jazz fans, and they only wanted to see George play so often. This is no reflection on George. Talented as he was, he could only keep drawing people for so long. Frank Sinatra, could probably not keep a Milwaukee club filled, week after week, for more than a year or so. Milwaukee was not New York or Los Angeles, after all. In point of fact, a few years after George had been involved with Pritchett's, his old boss Buddy Rich had quit the road, and decided to open a club in New York called Buddie's Place. The club did very well, initially, but after some time passed, even Buddy Rich could not keep a club filled, even in the city of New York. He closed his club, formed a new band, and hit the road again, staying with the new band until his death in 1986. There were other reasons though, and eventually there was a sense of things beginning to unravel. George could be pretty obnoxious when he was drinking, which was pretty much all of the time while performing. He could be very funny, and had a sharp, sometimes cutting sense of humor, but he also rubbed many people the wrong way. I remember one particular incident where a family had brought their son out on his birthday, to see George. The boy looked to be twelve or so, and he had a song request. I don't recall the song, but it wasn't one that George liked, and he asked the boy if he was sure he wanted to hear that song. When the boy nodded his head, George said "OK little bonehead, in the next set." The family got up and left. He may not have meant anything by it, but he alienated a large number of people by such unthinking antics. For months, this huge room had been packed, and everyone was making money, and having fun. The problem with such a large room is that, even a slight drop in business, makes the place look empty. A crowd of 100 people who came to see George, a respectable crowd by any account, would make Pritchett's look like an empty cave. George came up with a couple of solutions. The first was open jam nights, where local musicians came to perform with George. These could be other club musicians, performers from the Milwaukee Symphony, out of town visitors, working musicians, or even some of George's students. This really charged the atmosphere, and made Pritchett's a place where musicians, and music enthusiasts began to congregate, and interact. It was a sort of a school, musical lab, and exhibition, all rolled into one. George could be a rough teacher and a hard master. You didn't want to be up on the stage with him, if you were not able to deliver.  The other solution was brought

about by George's realization of what was happening and the fear

that he would give himself too much exposure, and prematurely end

his career. Pritchett's would bring in guest musicians. This would not

be the students, locals, and music enthusiasts of the jam nights, but

would be accomplished professionals of national and world repute. There

would be a series of shows, for which an admission would be charged,

featuring nationally known top flight jazz artists. George would play

from time to time, but he would no longer perform every night.

The other solution was brought

about by George's realization of what was happening and the fear

that he would give himself too much exposure, and prematurely end

his career. Pritchett's would bring in guest musicians. This would not

be the students, locals, and music enthusiasts of the jam nights, but

would be accomplished professionals of national and world repute. There

would be a series of shows, for which an admission would be charged,

featuring nationally known top flight jazz artists. George would play

from time to time, but he would no longer perform every night.

Years latter, during a radio interview, he brought up the subject of visiting musicians, and of touring. Back when he had started out, he said, you worked a town. People went out every night, and wanted to hear music. So you would work the south side for a few weeks, until you went stale there, and people stopped coming to see you, then go work the north side for a few weeks. You might then work some downtown clubs for a while, and then work the east side, or one of the suburbs. By the time you finished this cycle, people on the south side were ready to go out to see you again, and so it went But this had been the fifties, and early sixties, and things had changed. Well things do change, people were now staying in more, and were willing to travel farther when they did go out. There were also far fewer clubs, than had once been the case, so this called for a new strategy. George's idea was that instead of working a town, you worked the whole country. You played to bigger crowds, for shorter periods of time, and then you moved on to another city. So you would work Milwaukee, until you went stale there, and then go down to Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, or even Madison, and Green Bay. You drew a large crowd, the people who wanted to see you came out, and then you moved on. In a few months, or a year, when you got back to that town again, the people were once more, anxious to see you. This was a pretty good plan, and it's logic can be clearly seen by what happened to Buddy Rich. He had great success on the road, playing to sell out crowds of enthusiastic fans, but could not keep a club filled, even in New York City. What George had been hoping for, with Pritchett's, was a sort of home base for him, a jazz showcase which would host visiting artists while he was touring, but would always be his place when he wanted to work at home. This may have actually worked out, as the visiting artists seemed to draw all right, and George was still very popular, but there was one other problem. Never go to work for, or go into business with, your family. George's brothers Bob and Mel were very enthusiastic about the whole business, and were delighted with the great success of the club, but there was something odd going on with his brother Dick. To this day, I still don't know what the problem was with Dick. It may have been jealousy, after all it was Dick who wanted to be a guitarist, and who had first introduced his little brother George to the guitar. Who can say? Whatever the problem, I latter learned that Dick had always been the voice of doom, right from the beginning. It was Dick who complained constantly that everything cost too much, people would not come, we already have a bar downstairs, or we could really do better things with this space. Once the die was cast, it was once again Dick who had nothing good to say about the way the place was being run. His criticisms also began to include personal attacks on his brother: George is a drunk, George can not be trusted, he is irresponsible, etc., etc. Mel was happy enough, and Bob was very enthusiastic, and liked the idea of being a club owner, and of being involved in the center of the burgeoning jazz scene; but the whole thing seemed to be just too much for Dick. Dick began to tell the bartenders to watch George, and keep track of how much he was drinking on the house. This was not out of brotherly love, but was out of a fear that George was drinking up too much of the profits. Most of the bartenders knew and liked George, and so took little note of Dick's badgering. Certainly George drank while working, as he had for most of his life, but he performed marvelously, and drew people in. Much of what he drank was bought for him by appreciative customers, and so profited the business, though at the expense of George's health. At about this time, George played at a Jerry Lewis telethon, for Muscular Dystrophy. Milwaukee was chosen that year to be one of the showcase cities for the event, so we had some national celebrities come here. The host was Arte Johnson, from the Rowan and Martin laugh in show, and the show was presented in the ballroom of what was then the Marc Plaza (now the Hilton). Arte Johnson was a fairly big comedy star in those days. Like most people hearing George perform for the first time, he was amazed at the speed and brilliance of George's playing. When the usual questions, offers, and suggestions came in, George was flattered, but uninterested. He had his club with his brothers, he had a new young son, and his family life, though not ideal, was going as well as it ever had. He was popular, well liked, and well connected in Milwaukee, and he was happy. George was on top of the world, and he saw no reason to go to another world, where he would have to work his way up all over again. Unknown to him at the time, his world would soon turn. The phenomena of Pritchett's was brought to an abrupt stop by family infighting. I was just a teen ager at the time, and did not witness the events which led to the disbanding and closure of the club, but I do know that, as with much of the misfortune that plagued George's life, alcohol was involved. The brothers were gathered at the club one night. George had been drinking, as had Bob. Mel may have had a bit also, but not Dick. There was a fight, over something, I never found out what, and the four ended the partnership then and there. Pritchett's disappeared from the Milwaukee jazz scene. It closed for a while, was used for private parties, and eventually reopened, as a bar and dart room. George's albums are on CD there, in the juke box, so it is still possible today, for some pocket change, to hear George's old music, played in George's old room. |

||||

Things were bad, work was hard to find, he would soon be separated from his family, and his health was not good. The eighties were not good years. George took on some students, whom he taught at home, and seemed to really enjoy teaching. They would gather at the house, on the weekend, and polish their style with George. He became a mentor to many young musicians, at this time. This was just as well, since club work was disappearing in Milwaukee, particularly for jazz musicians. He was very angry, during this  time. He knew that his talent had earned him better than

this. He should be famous, and here he was not even able to find

steady work as a musician. He had been particularly wounded by the

way that his brothers had turned on him. He had always set great store

in them, and could recall having been able to count on them as a child,

when they were his big brothers, and his father could not be counted

upon. Now they had abandoned and rejected him. He had also used up a

lot of favors, really almost used up the town. He owed money, and saw

few options. He began to consider the mantra of the past twenty years,

constantly repeated, that he should get out of Milwaukee.

time. He knew that his talent had earned him better than

this. He should be famous, and here he was not even able to find

steady work as a musician. He had been particularly wounded by the

way that his brothers had turned on him. He had always set great store

in them, and could recall having been able to count on them as a child,

when they were his big brothers, and his father could not be counted

upon. Now they had abandoned and rejected him. He had also used up a

lot of favors, really almost used up the town. He owed money, and saw

few options. He began to consider the mantra of the past twenty years,

constantly repeated, that he should get out of Milwaukee.It was getting harder to find George now. He would be playing in some little out of the way spot, or perhaps on an improvised bandstand at a bar in some residential neighborhood. I recall picking him up once, at a bar on Milwaukee's south side called Ralph's. I was a grown man by this time, and a former class mate of mine was working the bar. This is when what had happened to my dad's life first struck me. Here he was playing to a neighborhood bar with a younger crowd, younger musicians, and a staff of about my own age, but he was now in his forties. He had probably played to the parents of some of these people, but now the parents had moved past this stage, while their children took their place. George was still at that same point in his life, as if he was trapped, unable to move forward. Indeed, since his glory days at Pritchett's, he had moved considerably backward. It's not that this was a bad place, or that dad seemed so miserable. In point of fact, I remember him being very cheerful, and happy to see me. He seemed to get a bang out of the fact that the bartender had been a schoolmate of mine. What was so sad to me was that, after having spent the entire prime of his life hustling, and developing his skills, here he was still hustling club jobs, playing for a new crowd of young people, and involved in the rapidly diminishing club life, while the rest of his generation had moved on. The steady work was gone, and he often found himself working a few nights a week, if that. To many people, George was getting to be a memory, a musician from the past, who they remembered fondly. He was getting by, to a certain extent, on favors from old friends. He found cars through friends, and no longer owned his beloved Volkswagen beetles. They had become popular cars, and he could no longer afford them. Where once, everyone knew about him, now those who remembered would ask "What's George up to these days; is he playing anywhere?" All too often, he was not.  In a newspaper interview, right

before he left Milwaukee, George asked "Why is it that the best musicians

in town, only work two nights a week?" In 1984, tired of it all,

and not feeling anything to hold him in Milwaukee, he went down to

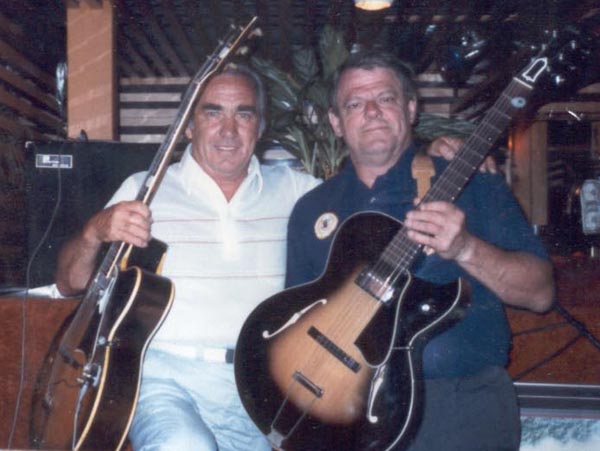

Florida, to hook up with another jazz guitarist, Don Momblow. Don

had been a Milwaukee guitarist for years, and had also been a booking

agent for entertainment at some of the area's local events. He too,

had felt the squeeze, and had left Milwaukee years ago, to do resort

work in Florida. The two hooked up, and booked themselves as "Two

Guitars".

In a newspaper interview, right

before he left Milwaukee, George asked "Why is it that the best musicians

in town, only work two nights a week?" In 1984, tired of it all,

and not feeling anything to hold him in Milwaukee, he went down to

Florida, to hook up with another jazz guitarist, Don Momblow. Don

had been a Milwaukee guitarist for years, and had also been a booking

agent for entertainment at some of the area's local events. He too,

had felt the squeeze, and had left Milwaukee years ago, to do resort

work in Florida. The two hooked up, and booked themselves as "Two

Guitars". They did pretty well, and were quite popular. For some reason, they came back up to Milwaukee. They found work here, at a variety of clubs, and events, but eventually they went their separate ways. Momblow was also a pretty heavy drinker, with similar bad effects on his own personal life; but that's a story for someone else to tell. It's good that they found each other, in the eighties; but even so, their common bond seemed to consist of drinking, and playing guitar. Dad used to call Don "Mumbles, and the friendship became very close, almost like that of a couple of kids. They worked together, went out together, were often on the phone together, and really helped each other out. They were good friends, at a time when each really needed a good friend. Having recovered a bit, from his malaise of the previous years, George put together a new band, and got himself a new club. It was on Milwaukee's near south side, right by the freeway, and he called it The Guitar. It was a small place, not much more than a corner bar with a stage, but George was hoping that with his new home base, and his new band, he could stage a come back. He found a good friend, and partner, in Manual Guerra, a local mechanic, garage owner, musician, and jazz enthusiast. Manual would eventually get sent to prison on drug charges, in a case where George was also implicated, and would not be out until years after George's death. George had about two years left to live. |

||||

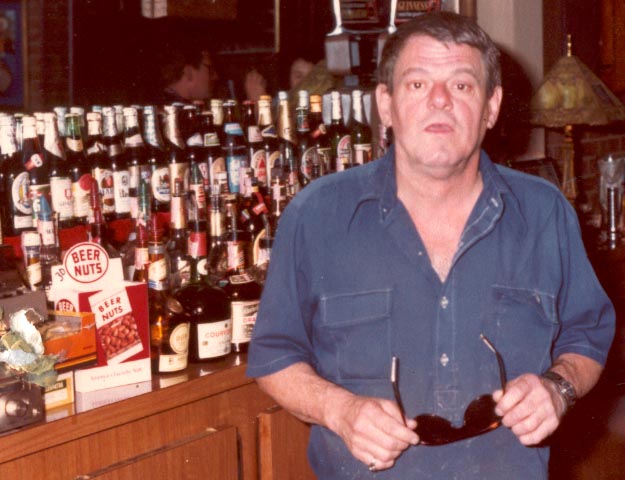

Towards the end, George's

life became a sort of a house of cards. His health was very bad,

he had financial problems, and he had gained a reputation as being

unreliable. For years, he had routinely worked very drunk, night

after night. This had altered his behavior to the point where many

of the younger generation who now came to see him, came as much to witness

his outrageous behavior, as to hear him play. It also ruined his health.

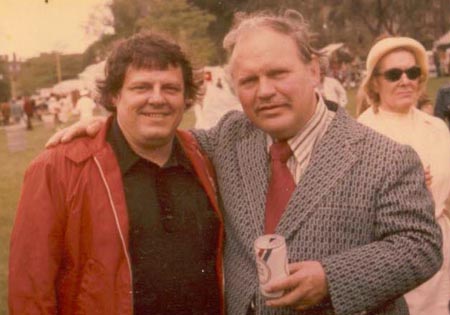

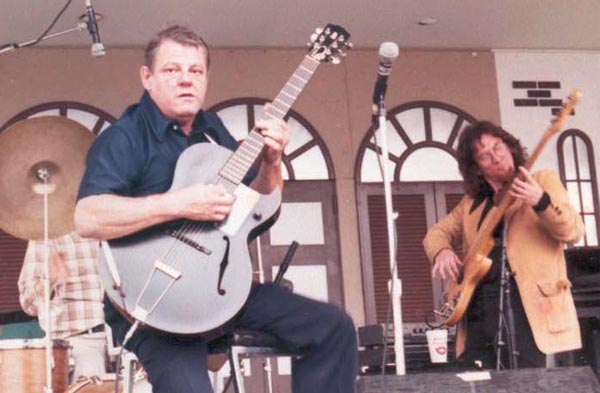

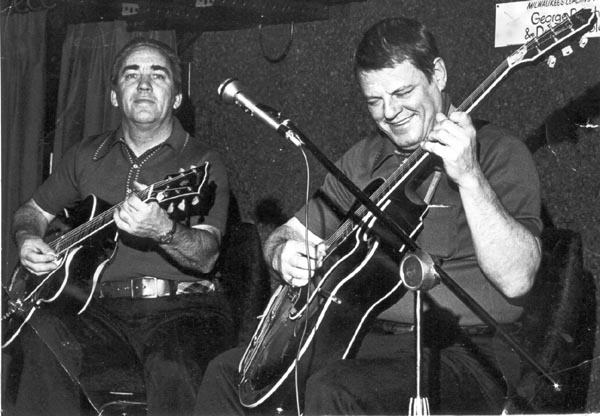

The photo shown at the top of this section, is of George on May 22, 1986,

at an event hosted at the War Memorial Center. He was 55 here, and had

fifteen months left to live. The photo just below that, shows him on

the Miller stage, at the Summerfest grounds. Interestingly, this is the

same stage that Buddy Rich had appeared on a few years previously (Click Here for Photos). Though George

had a circle of close friends, he had also stepped on many toes, and

many people actively disliked him. There were also some legal problems

in the works, for which George seemed likely to end up in prison. Towards

the end, with all of these forces arrayed against him, it seemed to be

simply a matter of which one would take him out first.

Towards the end, George's

life became a sort of a house of cards. His health was very bad,

he had financial problems, and he had gained a reputation as being

unreliable. For years, he had routinely worked very drunk, night

after night. This had altered his behavior to the point where many

of the younger generation who now came to see him, came as much to witness

his outrageous behavior, as to hear him play. It also ruined his health.

The photo shown at the top of this section, is of George on May 22, 1986,

at an event hosted at the War Memorial Center. He was 55 here, and had

fifteen months left to live. The photo just below that, shows him on

the Miller stage, at the Summerfest grounds. Interestingly, this is the

same stage that Buddy Rich had appeared on a few years previously (Click Here for Photos). Though George

had a circle of close friends, he had also stepped on many toes, and