|

Get Your Kicks

|

|

Index

These pages look best at 800x600, or 1024x768; at other resolutions

they can look downright strange.

An Introduction

Some background on a good friend, and faithful servant.

There are some things that we just can't

seem to part with, even when it is agreed, if less than unanimously, that

their time is past. We still romanticize the cowboy, the pioneer, and many

of the rest of the icons produced by the history of our short lived

nation, but their eras have passed, leaving nothing but a few old buildings,

some writings  and a great deal of lore and legend. Of course, these intrepid souls did

leave us one other thing. They left us the nation they built, the strongest,

most successful, most free, and most advanced nation in the world. One of

the more recently romanticized figures contributing to the making of our

country is, of all things, a road; it is Route 66. Route 66 tied the country

together in a very real and meaningful way, more so than anything since the

railroads had come through, many decades earlier. Formed in 1927, by a combination

of new construction, and the linking of older roads, it's time was publicly

declared past in 1960, though the last stretch was not officially bypassed

until 1985. In it's passing it has left behind it's own share of legend,

lore and chronicle, but it has left more. There are the small towns, and

villages, the rest stops, museums, points of interest, ghost towns, and tourist

traps. All of these remain along with a uniquely American style and love

of the road trip.

and a great deal of lore and legend. Of course, these intrepid souls did

leave us one other thing. They left us the nation they built, the strongest,

most successful, most free, and most advanced nation in the world. One of

the more recently romanticized figures contributing to the making of our

country is, of all things, a road; it is Route 66. Route 66 tied the country

together in a very real and meaningful way, more so than anything since the

railroads had come through, many decades earlier. Formed in 1927, by a combination

of new construction, and the linking of older roads, it's time was publicly

declared past in 1960, though the last stretch was not officially bypassed

until 1985. In it's passing it has left behind it's own share of legend,

lore and chronicle, but it has left more. There are the small towns, and

villages, the rest stops, museums, points of interest, ghost towns, and tourist

traps. All of these remain along with a uniquely American style and love

of the road trip.

Then there is the pavement itself, thousands of miles

of it. No longer a continuos stretch of highway as in it's glory days, but

broken into a collection of service roads, access points, frontage roads,

and state highways. In some places the pavement remains but has been abandoned

altogether. The end of Route 66 did not so much result in it's destruction;

instead, the road was discarded, with some parts being salvaged, and put

to other uses. The old pavement is nothing like the modern Interstate. The

remains of the old road consist of your basic two lane blacktop, with a yellow

line down the center to separate eastbound from westbound traffic. There

is no limited access here, and any road which crosses the old road produces

an intersection. Businesses built alongside the road are easily accessed

by driveways, pull outs, and service roads, just as on a city street. In

many ways, this is just what the old road was, a 2400 mile long city street,

the Main Street of America.

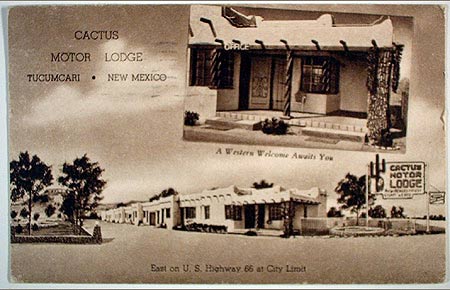

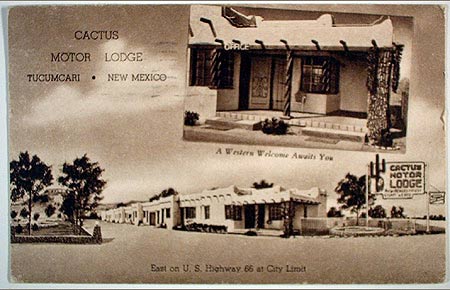

The old road has left more than legend, and more than

physical structure; it has changed us. It has instilled within us, the culture

of the road, the automobile, travel, and freedom. Truck stops got their start

here, along with motor courts, motels, road houses, drive ins, and a variety

of tourist traps. The oases, dear to travelers everywhere, was an innovation

of Route 66. The boredom of long road travel gave rise to a selection of

museums, gardens, zoos, and "educational" exhibits. Many new things were

tried here; some failed, some succeeded.

Route 66, and some other roads like it, prepared the

nation for the age of the automobile. It introduced us to the idea of the

motor tour, and weaned us from the old dirt tracks, trails, and named roads

carried over from horse and buggy days. These new roads had a far greater

role in renewing the sense of adventure and love of travel which so marks

our culture, than anything done by Ford, Chevrolet, or any of the other automobile

manufacturers. They also gave entrepreneurs, as well as big business

a taste of what services they would likely find a market for as America grew

more mobile. These roads then, were a learning tool, as well as a means of

getting across the country. The lessons learned on the old federal highway

system were not forgotten when the Interstate was being designed. Unfortunately,

a whole new series of lessons would need to be learned once the Interstate

was put into large scale use. The more studied approach of the Interstate

gave us broad straight ribbons of unbroken pavement, removing much of the

excitement, if not the terror, of traveling the old road.

How do you wax poetic about a road? Well, if the road

in question is Route 66, it is quite easy. How many Interstate highways have

songs written about them, or television series based upon them? What other

road has legions of travelers from all over the world, coming just to plant

their tires, and their feet upon it's pavement? The Route 66 television series

was less about the road, and more about what you might find traveling on

it. The same holds true about the song, and the legions of stories, movies,

and books about the old road. The television series sparked an interest in

the road in a new generation, even as The Grapes of Wrath had inspired the

generation before. A series of road movies, and a nostalgia craze for the

fifties, generated the same interest in yet another generation. Even after

over seventy years, and nearly twenty years past the time it was officially

closed, people continue to discover new things along it's length.

How do you wax poetic about a road? Well, if the road

in question is Route 66, it is quite easy. How many Interstate highways have

songs written about them, or television series based upon them? What other

road has legions of travelers from all over the world, coming just to plant

their tires, and their feet upon it's pavement? The Route 66 television series

was less about the road, and more about what you might find traveling on

it. The same holds true about the song, and the legions of stories, movies,

and books about the old road. The television series sparked an interest in

the road in a new generation, even as The Grapes of Wrath had inspired the

generation before. A series of road movies, and a nostalgia craze for the

fifties, generated the same interest in yet another generation. Even after

over seventy years, and nearly twenty years past the time it was officially

closed, people continue to discover new things along it's length.

This road carried the commerce of a nation. In many

ways it was a victim of it's own success. Stretches of the road were known

for the number of fatalities they produced; legendary names like "Dead Man's

Curve", were a reality out on some parts of "bloody 66." The existence of

the road, a link from, the heart of the country out to it's western edge,

encouraged people to travel, increasing traffic to levels not envisioned

by the original planners, and builders. Ironically, in recent times, the

Interstate which replaced sections of the old road has found itself the victim

of the same type of success.

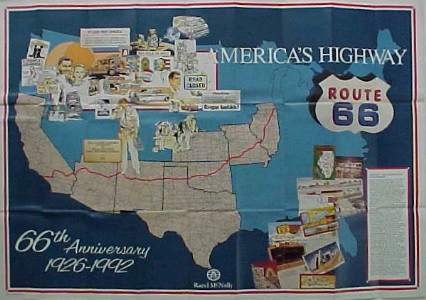

A few facts about the road, along with some comparisons

America's main street was one road in name only, at

least in the beginning. What was to become Route 66 started out as a collection

of county roads, state highways, and assorted trails (paved and unpaved).

These were chosen by a committee, to be integrated into what would become

the main road between the midwest, and the Pacific coast. Initially, the

only thing unifying this collection was a series of road signs, and a designation

on a map. Even so, this was a pretty ambitious undertaking, for 1927.

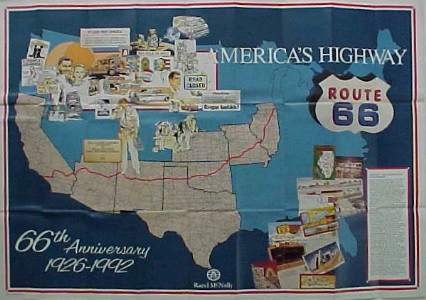

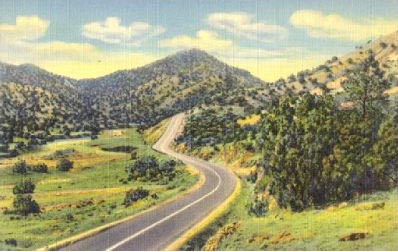

A look at the map gives some idea as to the extent of

the road, but does not give a clear idea of the range of climate and terrain

it traverses. The map is flat, not showing mountains, deserts, woodlands,

rivers, prairies, and the numerous other obstacles which plagued the first

adventurers to attempt crossing the continent, a century earlier. Thanks

to the pioneering efforts of roads like Route 66, and the follow up of the

Interstate system, we have come to take such ease of travel quite for granted.

In any other part of the world, a trip of such a length, over such a varied

terrain, would be a challenge at best, probably an adventure of a lifetime,

and life threatening at worst. Here, it is just a matter of hopping in the

car and bringing enough money (or the credit cards) to pay our way. To put

things in perspective, let's look at how the rest of the world gets around.

In Europe there has never been anything like a transcontinental

road. The closest thing might be the system of railways, and in particular,

the old Orient Express. Although the route varied throughout the years, it

ran from Paris to Istanbul, a distance of 3186 kilometers. This comes out

to something like 1800-1900 miles. Still not quite up to the distance of

Route 66. Counting the spur line which starts at Calais, and adds another

hundred miles or so, brings it within a few hundred miles of the length of

old 66. This takes the traveler across the entire width of Europe, crossing

the alps, a few time zones, and the borders of a number of countries. It

also takes the traveler through eastern Europe, and into Asia. Be sure to

bring your passport, lots of money (in various currencies, unless you wish

to wait in lines to have money changed over in the eastern countries), and

even more patience. The train, once the lap of luxury, has become a test

of endurance, temper, and in some cases courage.

In Russia, I have to admit that, the old road has met

it's match. Once again, we need to look to the railroads to find a contender;

there are no roads in the former Soviet Union to match Route 66. There is,

however, a railroad unique in the world. The Trans-Siberian Railroad is the

longest in the world. It's 6000 mile span reaches a quarter way around the

world (actually closer to a third, at it's latitude). If Route 66 were to

exist in Russia, it would stretch from Moscow, all the way across European

Russia, and over the Ural Mountains, until it ended deep within the desolate

wilds of Asian Russia. If you were to start Route 66 at the base of the Ural

Mountains, it would go through Moscow, pass out of Russia, and end somewhere

in the middle of Poland. Isn't geography fun!?

In asia, there is the Burma road which connected India,

with China, a distance of about about 700 miles, and took four years to build.

Hardly more than a glorified local spur, compared to old 66. Old 66, if built

in India, could completely cross the country, either running north-south,

or east-west. A more interesting comparison can be made by assuming Route

66 is started in Bombay, and heads, north, and then west. Such a road would

pass through Inda, Pakistan, Iran, and parts of Iraq, just about connecting

Bombay with Baghdad. If India 66 were to head east, it could connect Bombay

to Hanoi in Vietnam, or to Chunking, the former capitol of China.

Africa has no serious road, or railroad system, and

has had none since the passing of colonial times. Tribal wars, petty dictators,

poverty, and famine have destroyed much of the old infrastructure of colonial

days, and have seen to it that the population of Africa has had more serious

matters to busy itself with, than the building of roads. Even during colonial,

and pre colonial times, travel within central Africa was extremely slow,

and hazardous. The tsetse fly, host and carrier of sleeping sickness, meant

that there could be no travel by horse south of the desert. No horses meant

no real roads or trails of any size were built. No travel system of any length

was possible until the introduction of the railroad, by the colonial powers.

A road the length of Route 66, if built, would take one completely across

the continent in all but the widest portion. Even here, it would only miss

touching both oceans by a few hundred miles. Going from north to south, African

66 would take the daring traveler from the shores of the Mediterranean sea,

across the deserts of North Africa, and into the heart of the Congo.

As can be seen by the examples above, in any other

part of the world, the building of such a road, not to mention the support

structure, businesses, and stops along the way, would be a major achievement.

Here, the road is relegated to secondary status, and would have been discarded

altogether, were it not for the interest shown by tourists. In America,

this 2400 mile stretch of pavement passes through big cities, small towns,

8 different states, desert, mountain, prairie, woodland, and farmland. It

passes through some of the richest, most productive farm land in the world,

and through some of the most barren and sterile areas on the planet. At certain

times of the year, the road is capable of taking you from freezing cold to

unbearable heat. You can cross rivers swollen to flood stage, and a day or

two latter pass through dry areas where no water flows, and there has been

no rain for months. People talk funny, in some of the places the road takes

you, though you will be too polite to say so. In turn, these people will

be too polite to tell you that, to them, you talk funny too. The road itself

says nothing, merely humming contentedly beneath your tires.

Unlike the modern interstate, which merely connects

the nation, Route 66 actually joined it. It is possible to travel from one

end of the country, to another, via the interstate, without ever driving down

a city street, or actually seeing a city proper. We may drive through cities,

on the interstate, but we never really have to enter them. This kind of travel

was not possible on the old federal highway system, of which Route 66 was

a part. This was the reason for it's popularity, and was also what brought

about it's demise.

The Mother Road

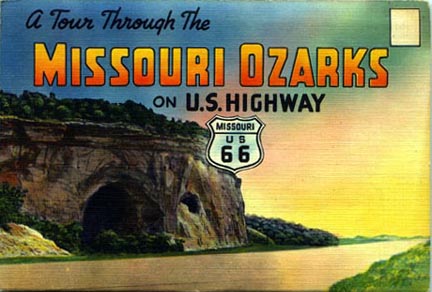

Route 66 followed many of the historical paths of pioneers,

and explorers. The Osage Trail, and the Santa Fe trail are just two of the

many legendary routes which grew from tracks into the wilderness to become

local roads, then state or county highways, and then finally became part

of route 66, as a part of the Federal Highway System. Many parts of the old

road started out as Indian trails, before the coming of the white man. Many

more were used by settlers, wagon trains, and particularly as military roads.

As cars began to dominate as a means of everyday transportation, it became

pretty apparent that, for long distance transportation, the odd patchwork

of roads crawling and twisting through the countryside, sometimes connecting,

sometimes not, were unsuited to our new found mobility.

Plans were begun in the early twenties, and by 1927,

the road itself came into being. In many ways these federal roads were the

final end to the old cowboy, pioneer, and trail system, and ushered in the

new era of automobile travel. Their time had come. A combination of production

line manufacturing, and post war prosperity, greatly increased the acceptance,

and number of automobiles in the nation. New technology developed for the

war and applied to peace time products, greatly increased the speed, power

and reliability of the new breed of cars on the road. It was now possible

to own, and operate an automobile without being a mechanic, or an adventurer.

It was also possible to acquire a car without being wealthy. Added to all

of this was the restlessness that always follows the end of a major war.

Young men displaced from society, struggled to find their purpose; but there

was more to the perceived need for these roads, than all of this.

Plans were begun in the early twenties, and by 1927,

the road itself came into being. In many ways these federal roads were the

final end to the old cowboy, pioneer, and trail system, and ushered in the

new era of automobile travel. Their time had come. A combination of production

line manufacturing, and post war prosperity, greatly increased the acceptance,

and number of automobiles in the nation. New technology developed for the

war and applied to peace time products, greatly increased the speed, power

and reliability of the new breed of cars on the road. It was now possible

to own, and operate an automobile without being a mechanic, or an adventurer.

It was also possible to acquire a car without being wealthy. Added to all

of this was the restlessness that always follows the end of a major war.

Young men displaced from society, struggled to find their purpose; but there

was more to the perceived need for these roads, than all of this.

After the First World War, the nation roused itself,

looked around, and seemed to get a sense of itself being something other

than a collection of rogue states, cowboys, farmers, and country cousins

living in the shadow of their European parents. This was when we began to

see ourselves as a great nation, and first realized that we were a world

power. The First World War had been a case of the new world coming to the

aid of the old. Yet, as we began to take ourselves seriously, we began to

note some strange discrepancies. There were parts of this new world power,

that were nearly inaccessible, while many areas seemed scarcely to have changed

since the days of the pioneers.

One gauge by which the cohesiveness of of a civilization,

and the stability of it's culture can be measured, generally has to do with

the speed at which communications, and travel can occur, and the dependability

of the means of accomplishing these. Using this gauge, the United States was

not what you could really call a unified nation, for much of it's existence.

At the time the new roads were being considered, radio was just beginning

to enter it's golden age, and the telephone was just starting to to gain ground

on the telegraph. Long distance phone calls were a bit of a hit and miss

venture. Communication through the mails was erratic, and sometimes undependable,

but was regular; transportation was a different matter.

Even after the first world war, the major mode of long

distance travel was by train. The major routes were those  laid down during the days of the frontier, and the wild west; it seemed that

in some cases, the trains themselves were not much newer. Yet these vintage

corridors were largely what linked the nation, moving it's commerce, keeping

it connected, fed, and supplied. The railroads were one of the first real

monopolies in this country, and travelers were limited to the routes, schedules,

regulations, and limitations imposed by the railroads.

laid down during the days of the frontier, and the wild west; it seemed that

in some cases, the trains themselves were not much newer. Yet these vintage

corridors were largely what linked the nation, moving it's commerce, keeping

it connected, fed, and supplied. The railroads were one of the first real

monopolies in this country, and travelers were limited to the routes, schedules,

regulations, and limitations imposed by the railroads.

There were roads, of course, but these roads were as

old, if not older, than the routes the trains traveled. Many were little

more than trails. The long distance traveler could expect, at the very least,

to become lost. Maps were poor, road markings almost non existent, and services

hit or miss. From the road itself, the traveler could not know what to expect.

There was no consistency. A road could be a mud track, paved dirt, gravel,

stone, or asphalt. Even more important, was the chance that a given road

may or may not have connections to other roads. For the transport of goods,

the roads were not really an option, except for local cartage.

The federal highway system, took us from trails to

superhighways It is sometimes difficult for us to understand just how much

the new roads unified the country, and changed the way we think about travel.

Fifty years before the coming of the federal roads, wagon trains had still

headed out west. The last great land rush took place, in Oklahoma, less

than forty years before. It is ironic that many of those involved in that

final rush would find themselves, or their children, on the road escaping

the devastation of the dust bowl years.

During the 19th century, the various homestead acts

had done a good job of spreading the population, and filling the country.

The challenge now, would be to connect all the little nooks and crannies occupied

by a people who, in the space of half a century, had filled a continent.

Stops along the way

One of the big attractions of "The Main Street of America"

is that, in many ways, this is just what it was. Route 66 did not bypass

cities, or even seek to avoid them; it took us right through the heart of

them. In numerous small towns, and big cities, Route 66 takes one down Main

Street, Central Avenue, or First street. These main thoroughfares were chosen

because, as main streets, they were generally the widest, smoothest, straightest,

and most direct routes through town. Most were already connected to county

or state roads, many having gotten their starts as local roads around which

their towns had grown up.

Actually, this jumping from town to town was not too

different from the way that travelers had traditionally covered long distances.

Back before the federal highways, and before the improvement of the maps,

the long  distance traveler would need to go from one city to another, seeking the

road in each town which would lead to the next. In order to keep from dead

ending in the middle of nowhere, the wise traveler would generally plan his

route to lead from one major city to another. So the new federal roads were

laid out to follow the cities which preceded them.

distance traveler would need to go from one city to another, seeking the

road in each town which would lead to the next. In order to keep from dead

ending in the middle of nowhere, the wise traveler would generally plan his

route to lead from one major city to another. So the new federal roads were

laid out to follow the cities which preceded them.

In other cases, the towns grew up along the road, starting

out as collections of businesses geared to serve the needs of the traveler.

Route 66 has been called, a single city with only one street, though that

street is 2400 miles long. It can certainly seem that way, particularly when

passing through the tourist traps, and garish little towns designed to entice

the traveler. The best of these little towns were delightful attractions

in their own right; the worst were little more than speed traps, and places

to get overpriced food, and lodging, both of dubious quality. Of course,

half of the fun and adventure of travel is learning to discern the bad from

the good, seeking out the latter.

Seasoned travelers share their knowledge, and lore

of the road. A common bond of shared experience links them all. Every traveler

on Route 66 has seen the big cross, the blue whale, the tilted water tower,

the Cadillac Ranch, and the various art deco gas stations, along with numerous

trading posts, stands, and assorted roadside stops. So perhaps you stopped

at the trading post of Chief Yellow Horse, and perhaps you did not, but you

did pass it, and see it, as did all of the other travelers on the road. Then

there is dinner at Ollie's in Tulsa, or perhaps at the Dixie Trucker's home

in Illinois. You may have had a custard at Ted Drew's in St. Louis, or tried

the 72 ounce steak at the Big Texan in Amarillo. Not all travelers stopped

at the same places, but all were exposed to the same variety. This gave a

certain similarity of experience, but made each journey, and each traveler's

individual perceptions of the road, just a bit unique.

There is more to the old road, however, than places

to eat, or stay, and places to buy trinkets. One of the more interesting,

and hopefully enduring, legacies of the old road comes from all of the cities

and towns stretched out across it's length. Some were never anything more

than little stops to eat and get gas (so to speak), while others were large

cities which long predated the existence of the road. All became part of

it's substance, coloring, and flavoring it with their own unique styles,

even as they were colored and flavored by the road. Regions too, added their

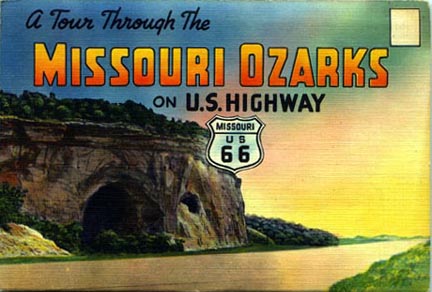

share to the allure of Route 66. The Midwest, the Southwest, California,

and bits of the south, all added to the experience of traveling through the

breadth of America on Route 66.

There is more to the old road, however, than places

to eat, or stay, and places to buy trinkets. One of the more interesting,

and hopefully enduring, legacies of the old road comes from all of the cities

and towns stretched out across it's length. Some were never anything more

than little stops to eat and get gas (so to speak), while others were large

cities which long predated the existence of the road. All became part of

it's substance, coloring, and flavoring it with their own unique styles,

even as they were colored and flavored by the road. Regions too, added their

share to the allure of Route 66. The Midwest, the Southwest, California,

and bits of the south, all added to the experience of traveling through the

breadth of America on Route 66.

Chicago, St. Louis, Oklahoma City, Los Angeles, and

the other big cities along the way, add a welcome bit of civilization to

travel along the road. They are good places to stock up on food, do a bit

of shopping, and perhaps stay in a fine hotel. They do make their own contributions

to the journey, but they are the public face of the old road. Though each

large urban area has it's own local flavor and history, most have been homogenized

somewhat, to the extent that most have the same chain stores, restaurants,

and generic "big city" way of doing things. The private face, and the heart

of the road is contained within the cities, and small towns which grew up

and out of it. These special places are sometimes unique to the point of

being eccentric.

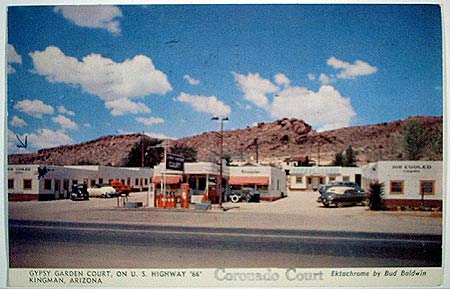

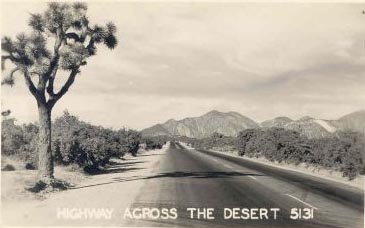

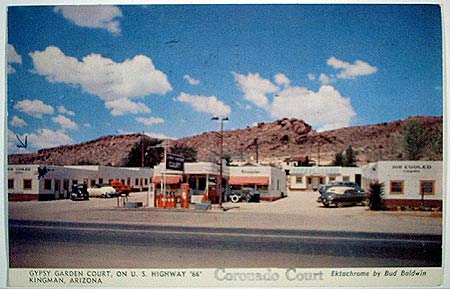

The more out of the way, and the more dependent on

the road, they are, the larger the amount of eccentricity.  Some of the high desert mining towns in Arizona, are particularly unique.

Hackberry, and Seligman seem like little more than collections of shacks.

Oatman with it's free ranging wild burros, or Kingman, climbing up the side

of a mountain, surrounded by high desert, and twisted roads, seem somehow

otherworldly. In California, the little hamlets of Amboy, Newberry Springs,

and Bagdad seem to define the notion of the little town in the middle of

nowhere. Set in the heat of the desert, amidst dried out lake beds, there

is no earthly reason for these towns to be here. There is no industry, no

hope of agriculture, and no agreeable climate. The only reason these towns

ever came to be, was the presence, and the need to service, the road.

Some of the high desert mining towns in Arizona, are particularly unique.

Hackberry, and Seligman seem like little more than collections of shacks.

Oatman with it's free ranging wild burros, or Kingman, climbing up the side

of a mountain, surrounded by high desert, and twisted roads, seem somehow

otherworldly. In California, the little hamlets of Amboy, Newberry Springs,

and Bagdad seem to define the notion of the little town in the middle of

nowhere. Set in the heat of the desert, amidst dried out lake beds, there

is no earthly reason for these towns to be here. There is no industry, no

hope of agriculture, and no agreeable climate. The only reason these towns

ever came to be, was the presence, and the need to service, the road.

What today strike us as a bunch

of sleepy little towns, were raucous places on the old road. They may become

lively again, as, like so many of the youthful travelers which have passed

through them, they seek to find their place along the road. Winslow, and

Tucumcari in particular, were known as busy, lively places. Williams had,

for years, been the jumping off point for the Grand Canyon. This is an honor

it is seeking to regain, by an extensive series of improvements, and tourist

attractions, including a regular steam train into the park. Then there are

the deserted places like Twin Arrows, Two Guns, Allenreed, and Glen Rio,

or the nearly deserted places like Meteor City (Pop 2). The old road takes

us through all of these places, some familiar, and some unheard of, except

by the  locals.

locals.

It also takes us into the countryside. The language

was carefully chosen here: where the Interstate takes us through the countryside,

the old roads took us into them. Though we have become largely a nation of

cities, and urban dwellers, such was not always the case, and even today is

not entirely the case. Besides a glimpse of our rural culture and heritage,

these country roads also take the traveler through the raw geology, and geography

of the continent. Unlike the Interstate, these older roads, permit pulling

over, getting out, and doing a bit of exploration. There is really much to

explore here. No matter what the climate, or part of the country you come

from, old 66 is guaranteed to take you through the different and the unfamiliar.

Aside from the cities, and the countryside, Route 66

gave the traveler plenty of the new and unfamiliar to explore. The meteor

crater is just off of the road, as are the Petrified Forest, Painted Desert,

and the Grand Canyon. Sandia, where nuclear weapons are developed and built,

stands near the road, along with the Atomic Missile Museum. You can sleep

in a wigwam, or in a room, and a bed, where Elvis once slept. You can also

sit on the back of a statue of a giant jackrabbit (complete with saddle),

and enjoy a nice cool cherry cider in the heat of the Arizona desert. You

may find yourself doing many things that you would never think to do back

home.

Where the modern interstate impairs and inhibits us

from stopping, the old road practically insists upon it. Where the Interstate

seems a bit ashamed of some of the places through which it passes, isolating

us, and hustling us along, the old road welcomes exploration, as if proudly

showing off the places it has collected to itself in it's wanderings.

Defining the era of the American Dream

What is it about old 66 that inspires such devotion,

fanaticism, and even feelings approaching love? Certainly, it is not the pavement

itself; there is no shortage of two lane blacktop roads in the world. It

can not entirely be a love of the cities, and places along the road. Though

some of these locations are quite nice, others are very unpleasant indeed.

Could it be the freedom of the road? Well, perhaps a bit, though the Interstate,

sanitized as it may be, is faster, safer, smoother, and has better services

than the old road ever offered.

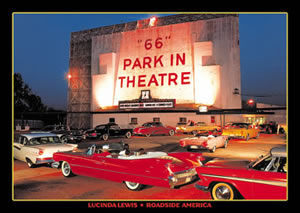

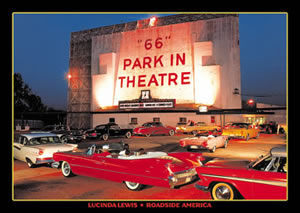

Route 66, along with a few other cultural icons, became

a focal point for an idealized America. The fact that it was decommissioned

at about the same time that many had given up, or lost their faith in the

old ideals, left it permanently associated with them. When, in latter years,

we discovered that we missed much of what we had discarded, it was natural

for us to search for these things in the places they had last been seen. Some

other expressions of freedom, confidence, and optimism, related to our love

of the road are:

- Drive in movie theaters

- Drive in (not drive through, an invention of the interstate) restaurants.

- Muscle cars

- Service stations (and they meant it).

- The family vacation

- National (and state) parks

- Little towns

There is a sort of a combination of quaintness, excess,

wholesomeness, and self indulgence that we associate with the bygone days

of the old American Dream. Certainly many other versions of the American

Dream have risen, but there is something special about the post war boom,

optimism, power, and sense of purpose that is longed for, even by those who

helped bring about it's demise. The social activism, sexual revolution, new

politics, and self awareness of the sixties, and seventies toppled much of

the aura of old America. Though few people miss the racism, quiet hypocrisy,

and mild paranoia of those days, our "progress" has not come without a price.

In curing, or trying to cure many of our former social ills, we have unwittingly

discarded much that was of real value to us. It seems like a case of "the

operation was a success but the patient died." The old evils have been replaced

by a set of new ones, less apparent, more complex, and more difficult to

deal with. They have been replaced by the hypocrisy of political correctness,

a distrust of our own government, loss of faith, loss of confidence, and loss

of belief in our own culture and morals.

There is a sort of a combination of quaintness, excess,

wholesomeness, and self indulgence that we associate with the bygone days

of the old American Dream. Certainly many other versions of the American

Dream have risen, but there is something special about the post war boom,

optimism, power, and sense of purpose that is longed for, even by those who

helped bring about it's demise. The social activism, sexual revolution, new

politics, and self awareness of the sixties, and seventies toppled much of

the aura of old America. Though few people miss the racism, quiet hypocrisy,

and mild paranoia of those days, our "progress" has not come without a price.

In curing, or trying to cure many of our former social ills, we have unwittingly

discarded much that was of real value to us. It seems like a case of "the

operation was a success but the patient died." The old evils have been replaced

by a set of new ones, less apparent, more complex, and more difficult to

deal with. They have been replaced by the hypocrisy of political correctness,

a distrust of our own government, loss of faith, loss of confidence, and loss

of belief in our own culture and morals.

In the fifties, and into the sixties we knew we were

the wealthiest, most powerful, and advanced country in the world. More important

though, we knew we were the moral, and cultural superior of every other nation

on Earth. We knew we were right. As much as we today worship the self, independence,

choice, and individuality, we long for the stable family with mom at home,

dad at work, junior and sis at school, and the certainty that tomorrow would

be better than today. What we also long for, despite our new worship of "open

mindedness" is the certainty that we are right, that we are on the right

track, fighting the good fight, and making the world safe for democracy,

that we can trust our leaders, our neighbors, and ourselves to do the right

thing.

That sense of identity, security, correctness, and

purpose is what we so long for, when we go searching for the old 66, and

the nation it served. What is surprising is that, in many places, it is still

there. In traveling the old road, I have seen small towns and big cities

in the process of rebuilding themselves. This was particularly apparent in

places like Oklahoma City, and Tulsa. Then there is the stubborn pride of

places which have seen better days, but cling proudly to their old identities

as they seek to make a comeback, places like Tucumcari, NM. Galena, KS. and

Williams AZ. There are also the timeless places, which seem unaffected by

the road, or by much of anything else. Some are large cities, like Chicago,

and Los Angeles themselves, while others are a bit more modest, places like

Flagstaff, or St. Louis. These were all great cities, filled with a great

people. Some remain so, while others struggle on.

So we travel the old road, buy the souvenirs, listen

to the old music, and make a fad out of "retro" fashions, dances, cars, and

furniture. We also keep a close watch for Elvis.

Passage into legend

The new system of Interstate Highways, spelled the

end of the old Federal Highway System. From 1960, when it's end was pronounced,

to 1985 when the last section was bypassed, and it's traffic routed to the

Interstate, Route 66 began to die the slow death of 1000 cuts. About the

time that the road was being phased out, it began to attract it's greatest

following. When Route 66 first aired as a television show, sections of the

road had already been bypassed. The vast majority of the road was still there,

but the writing was on the wall; the end was clearly near. Many people desired

to travel the legendary road just once (or just once more) while it could

still be done.

The road did not die easy. Almost everywhere the Interstate

came to replace it, objections were lodged, injunctions were sought, and

protests were organized. This was done, in many areas, for sentimental reasons,

but in many others the reasons were dead serious. The passing away of the

road was the death knell for many of the small towns, and hamlets which got

their living from it. It was also the death knell for many roadside businesses,

which would be inaccessible, or nearly so, from the limited access Interstate

which was to replace the old open access road.

Throughout the sixties, most of the road remained, and

it was still the preferred route across the country, but in the seventies,

the old road was noticeably truncated, broken up, and difficult to use as

a continuos highway. Road signs and markers were removed from city streets,

and rural highways, making the old road hard to find, and difficult to follow.

It was no longer clearly marked on maps. By the time the last stretch was

closed in 1985, only a few purists, or old timers, even knew how to find

the old road. Really by this time the road was already long dead. The final

stretch was kept open in Arizona by a series of legal maneuvers, but it's

closure was inevitable.

Most people paid little mind to the replacement of

the old road. This was progress, after all, and you can't stand in the way

of something so sacred. So the little towns died, or grew much smaller, the

old roadside businesses withered and faded to disappear, and the traditional

stopping off points were passed by. A few things began to strike travelers

about the new Interstate system, though. Traveling on it was deadly dull,

consisting of long unbroken stretches of concrete. Where was the romance of

travel?

The Interstate

It may seem that I have cast the Interstate in the

role of the villain in this story. In truth, I love the Interstate,

and travel it often. The Interstate is a great way to get around, within

it's limitations. These limitations are:

- You can't pull over, and can not easily get off. You are confined

to the road, except at the ramps.

- You can't get to anything, except by taking the nearest ramp and

then backtracking. Even this only works if there happens to be an access

or frontage road running alongside the Interstate; in many places there is

not.

- Land is expensive at exits. No longer can a little guy start a

small business, on the road, it is now all big sanitized chains.

- The Interstate bypasses the cities, and small towns along the way.

Of course, the Interstate is not without it's advantages. These are:

- The Interstate is fast.

- It is much less likely you will become lost.

- With some exceptions, the Interstate is much safer.

The Interstate has also done some harm to our culture,

and particularly to many of our larger cities. Those of us in our forties,

and older, may still remember the days when the new construction cut a swath

right down the center of town, removing the heart from many cities. Houses

were knocked down, businesses relocated, or shut down, and hundred year old

neighborhoods razed or at the very least partitioned. There were always rumors

circulating, or jokes being told about families barricading themselves in

their houses, and refusing to leave, or homeowners lying down in the path

of bulldozers. Most left, disgruntled, but without causing trouble, to settle

in new places.

Where the old road had taken traffic through city streets,

via a marked route, the new Interstate made no concessions, and seemed to

take little notice of the cities through which it was built. It became a

world of it's own, replacing rather than merging with the places through

which it traveled. Once the new superhighways were finished, the construction

crews would move on, and the city which had happened to be in the way, was

left to heal it's wounds as best it could. Many never quite healed right,

and even those that did were left somewhat disfigured. There was the physical

destruction of the parts of the city that the road went through, but there

was also the strange way that most cities had of adapting to the presence

of the new Interstates.

One of the first things that the presence of the freeways

did was to turn many of the downtown areas, and other business districts

into little more than staging areas for the freeway on ramps. In many places,

main roads, and side streets were made one way, or rerouted, to more efficiently

direct traffic onto the new freeways. Old photographs taken of the downtown

areas of most major cities will show streets lined with parked cars, sidewalks

filled with pedestrians, and a selection of busses, and streetcars. A contemporary

photograph of many of the same places will show only stalled traffic. Street

parking was eliminated so that new traffic lanes could be added to help handle

the load. This tended to make many downtown areas places to pass through,

rather than places to stop, but worse was to come.

As city business districts became less amenable to

casual wandering, People began to frequent them less often, and for shorter

periods of time. This had the predictable effect of stagnating much of the

traditional downtown commerce, and forcing the businesses depending upon

consumer traffic, to move out or go under. Over time, things became much

shoddier, and of smaller scale. Downtown areas became a bit disreputable,

and run down. This added further to their abandonment. So where could people

now go to shop?

The newly built shopping malls, out in the newly accessible

countryside, could provide for all of the shopping needs of the most voracious

consumer. Soon enough, even those who remained in the city, came out to the

malls. After all, they were so new, and so clean, not like the torn up downtown

areas of the city itself; also unlike the downtown areas, out in the malls,

you could actually park your car, and stay a while. They were also, relatively

safe. The downtown, and central areas of the city had started to become very

unsavory places, or at any rate, they had become places in which a certain

amount of caution need be shown.

What of the main streets through town, the ones which

people had traveled every day to get to work, or to shop? Well, most of these

city sections were bypassed, by the new freeways, and left to whither on

the vine. Most people took the freeway through town, rather than the city

streets, in order to avoid lights, and to make use of the faster freeway

speeds. This was a sort of a minor version of the disasters which befell

the towns being bypassed by the Interstate. This also had the effect of segregating

older parts of town, which had only been busy in the first place, because

they were the major routes through the city. Once alternate, and faster,

routes became available, there was little incentive to travel through certain

areas of town, making them isolated backwaters.

I used the word "segregating", to describe the cutting

off and containment caused by many of the new freeways; this word was not

completely chosen at random. Though there had always been racial segregation

in the country, the new freeways, by permitting the isolation of large sections

of the inner and central city, made the process much more complete. So just

as the civil rights movement was beginning to make some changes in attitudes,

and in law, the new fragmenting of the city helped to enhance the segregation

of the races. This point was emphasized by a footnote in one of the current

guidebooks to Route 66. It warns the reader about following the old road

through certain parts of the Chicago, and St. Louis areas, recommending that

the wary traveler bypass these places, and take the Interstate through town.

Had Route 66 remained the main corridor, and had the Interstate not cut off

these sections of town, they would not (could not) have been allowed to fall

to such a state. Since these neighborhoods became bypassed, and were no longer

"important" to the city at large, they were allowed to decay, and to become

dangerous. Rather than pulling together, insisting that these areas be fixed,

or fixing them directly, most of the middle class simply moved away from

them, escaping rather than repairing, the damage.

While construction of the new freeways was engaged in

tearing up the heart of the city, and fragmenting it, the freeways themselves

made the city easier to get out of. Once upon a time, you needed to live in

town to be close to work, schools, shops, and cultural activities, but not

any more. Now, a short drive on the Interstate could get you out in the country.

Little farming communities, and small towns out in rural areas, suddenly

became popular places for the newly mobile to live. This was probably the

worse effect it had on the cities, since it was now possible to simply ignore,

abandon, or discard them, in the minds of those who could move out. Twenty

years before, problems of crime, poverty, decay, and corruption, would have

had to have been dealt with; the coming of the freeways, made it possible

to simply move away from them. So cities became disposable, and large sections

of them were, in effect, disposed of.

With all of this moving out, commuting, and bypassing,

cities (now called urban areas to reflect the dependencies of the suburbs,

and satellite cities) became much more spread out. This made cars a necessity,

for even the most mundane things. It also made possible the large megamarket,

and mega store, effectively squeezing out the small shopkeeper. Suddenly,

everything became much more impersonal, farther away, and less intimate. The

idea of a functioning neighborhood went away. People began to shop, work,

and go to school, miles from the places where they happened to live.

On the other hand, the Interstate can get me anywhere

in the country within a few days. The urban sprawl it has fueled is good

or bad, as a matter of personal taste. I personally hate it, and hate the

blight it has contributed to in the cities. Having said this, I must admit

that I personally live in a far western suburb of Milwaukee, though I would

have probably stayed in the city had urban sprawl not so decimated the downtown,

raised the taxes, and siphoned off so many of the jobs, and culture of the

Milwaukee I had known as I was growing up.

Route 66 Today

So what has become of this famous, and beloved road? Well,

a number of things, depending upon which stretch of road you are talking about.

It seems as if the old mother road has gone back to it's roots, becoming

once again, a broken series of sometimes connected, but unrelated stretches

of pavement. In general, you will find the physical remnants of the old road

as one of the following:

- Frontage roads

- Business roads

- Paved over and integrated into the Interstate.

- Abandoned local dead end stretches

- Scenic, restored stretches

The most common use to which the pavement of old 66

is put, is as frontage roads, serving the Interstate which replaced it, and

providing local access for the people in the area, and the occasional tourist.

In many places the old road will veer away from the Interstate, and take

the traveler off the beaten path a bit. Some of these isolated areas are

treasures of lore, history, and local color; others are depressing bits of

abandoned America, left to ruin. In many other places, particularly in the

southwestern states the old road will run right alongside the Interstate for

miles. In many of these areas, it is nearly impossible to travel the old

road for any distance. The service roads, into which it has been transformed,

tend to be broken up at intervals by ramps, crossings, or even by the occasional

intrusion of the interstate onto the former roadbed of 66.

In medium to large cities, or areas of special interest,

the old road will become a business bypass. In most of these places it will

be called Business 40. The business roads, tend to go through either the

middle of town, or through special business districts on the outskirts. Often

they will do both, taking the traveler through busy areas full of shops,

malls, motels, and restaurants, before passing through the heart of the city.

These business loops can be a great deal of fun, particularly since the renaissance

and rediscovery of old 66. They are probably closer to the feel, pulse, and

old liveliness of the original 66, than any other place, including the restored

scenic sections.

In a few areas, 66 has been completely abandoned. There

is one long stretch like this, where the road crosses from Texas into New

Mexico. In this spot, the road has been abandoned because the Interstate

takes a shortcut. The road is still there, and it can be accessed by getting

directions from the locals. It starts out as a city street, which heads out

of town, and disappears into the desert/prarie. It is not closed off, nor

is it forbidden for travelers to embark upon it. This stretch has been abandoned

in the sense that it is no longer shown on maps, road crews no longer maintain

it, and there are no services along it's length, but it is still there. The

Texas/New Mexico border stretch is unusual, on most of these abandoned stretches,

the road has simply been cut off at both ends, by freeway ramps. Though these

sections are generally visible from the Interstate, and tend to run right

alongside it, they can be very difficult to access.

In recent years, people have been taking a careful measure

of the culture we have built for ourselves, and have found it wanting, in

many respects. In answer to the nostalgia created by this revisiting of the

past, many areas of old 66 are being restored, marked on special maps, and

are even seeing a return of the old style highway signs. The best section

of this type is probably the small section in Kansas, though there are significant

restored sections in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona. The midwest seems

to be the last section to revalue the old road, though Illinois, and Missouri

have developed some strong local groups. California, at the west end of the

road, is the state which practices veneration of the automobile, and of the

road more than any other. It has a number of organizations, museums, and

quirky little stops offs on the stretch of old 66 which passes through the

desert.

A New Life

Route 66, and many of the businesses found

on or near it, survive today on tourism. Rather than being a place to pass

through, Route 66 has become a place to be; everyone wants to travel the

old road. On my own travels I have seen individuals, and tour groups from

all over the world. A band of Austrian Motorcyclists pretty much paralleled

my own trip down the old road. I ran into them at Meteor Crater, the Petrified

Forest, and Painted Dessert, the Museum in Galena, and at the Continental

Divide.

All along the old route, the road is reawakening, though

in quite a different form. In the old days, this had been a working road,

but not anymore. Interstate 40 handles most of the commerce, travel, and

day to day business that once depended on old 66. Instead of trucks, salesmen,

relocating families, and business travelers, old 66 now gets tourists, travel

buffs, adventurers, and those nostalgic for the dreams of the past. The road

has become like one of those old steam trains that people pay to ride, or

rather like booking a passage on a cruise line. Many people seek it out to

travel it more for the journey than as a means to get to a destination.

This new lease on life, is by no means a resurrection

of the 66 that used to be. Rather, it is a phoenix risen from the ashes of

what was once a much different and larger animal. The reborn road is busy

enough to keep the little towns, and many of the small businesses along it's

path alive, but will never again have the volume with which to restore them

to their former glory. They will remain icons frozen in time, like the old

cowboy towns which thrive on what they once were. Legendary places from a

time when you could put the top down on your souped up car, throw a few things

in the back, crank the radio, and hit the road to get your kicks on Route

66.

and a great deal of lore and legend. Of course, these intrepid souls did

leave us one other thing. They left us the nation they built, the strongest,

most successful, most free, and most advanced nation in the world. One of

the more recently romanticized figures contributing to the making of our

country is, of all things, a road; it is Route 66. Route 66 tied the country

together in a very real and meaningful way, more so than anything since the

railroads had come through, many decades earlier. Formed in 1927, by a combination

of new construction, and the linking of older roads, it's time was publicly

declared past in 1960, though the last stretch was not officially bypassed

until 1985. In it's passing it has left behind it's own share of legend,

lore and chronicle, but it has left more. There are the small towns, and

villages, the rest stops, museums, points of interest, ghost towns, and tourist

traps. All of these remain along with a uniquely American style and love

of the road trip.

and a great deal of lore and legend. Of course, these intrepid souls did

leave us one other thing. They left us the nation they built, the strongest,

most successful, most free, and most advanced nation in the world. One of

the more recently romanticized figures contributing to the making of our

country is, of all things, a road; it is Route 66. Route 66 tied the country

together in a very real and meaningful way, more so than anything since the

railroads had come through, many decades earlier. Formed in 1927, by a combination

of new construction, and the linking of older roads, it's time was publicly

declared past in 1960, though the last stretch was not officially bypassed

until 1985. In it's passing it has left behind it's own share of legend,

lore and chronicle, but it has left more. There are the small towns, and

villages, the rest stops, museums, points of interest, ghost towns, and tourist

traps. All of these remain along with a uniquely American style and love

of the road trip.  How do you wax poetic about a road? Well, if the road

in question is Route 66, it is quite easy. How many Interstate highways have

songs written about them, or television series based upon them? What other

road has legions of travelers from all over the world, coming just to plant

their tires, and their feet upon it's pavement? The Route 66 television series

was less about the road, and more about what you might find traveling on

it. The same holds true about the song, and the legions of stories, movies,

and books about the old road. The television series sparked an interest in

the road in a new generation, even as The Grapes of Wrath had inspired the

generation before. A series of road movies, and a nostalgia craze for the

fifties, generated the same interest in yet another generation. Even after

over seventy years, and nearly twenty years past the time it was officially

closed, people continue to discover new things along it's length.

How do you wax poetic about a road? Well, if the road

in question is Route 66, it is quite easy. How many Interstate highways have

songs written about them, or television series based upon them? What other

road has legions of travelers from all over the world, coming just to plant

their tires, and their feet upon it's pavement? The Route 66 television series

was less about the road, and more about what you might find traveling on

it. The same holds true about the song, and the legions of stories, movies,

and books about the old road. The television series sparked an interest in

the road in a new generation, even as The Grapes of Wrath had inspired the

generation before. A series of road movies, and a nostalgia craze for the

fifties, generated the same interest in yet another generation. Even after

over seventy years, and nearly twenty years past the time it was officially

closed, people continue to discover new things along it's length.  Plans were begun in the early twenties, and by 1927,

the road itself came into being. In many ways these federal roads were the

final end to the old cowboy, pioneer, and trail system, and ushered in the

new era of automobile travel. Their time had come. A combination of production

line manufacturing, and post war prosperity, greatly increased the acceptance,

and number of automobiles in the nation. New technology developed for the

war and applied to peace time products, greatly increased the speed, power

and reliability of the new breed of cars on the road. It was now possible

to own, and operate an automobile without being a mechanic, or an adventurer.

It was also possible to acquire a car without being wealthy. Added to all

of this was the restlessness that always follows the end of a major war.

Young men displaced from society, struggled to find their purpose; but there

was more to the perceived need for these roads, than all of this.

Plans were begun in the early twenties, and by 1927,

the road itself came into being. In many ways these federal roads were the

final end to the old cowboy, pioneer, and trail system, and ushered in the

new era of automobile travel. Their time had come. A combination of production

line manufacturing, and post war prosperity, greatly increased the acceptance,

and number of automobiles in the nation. New technology developed for the

war and applied to peace time products, greatly increased the speed, power

and reliability of the new breed of cars on the road. It was now possible

to own, and operate an automobile without being a mechanic, or an adventurer.

It was also possible to acquire a car without being wealthy. Added to all

of this was the restlessness that always follows the end of a major war.

Young men displaced from society, struggled to find their purpose; but there

was more to the perceived need for these roads, than all of this.  laid down during the days of the frontier, and the wild west; it seemed that

in some cases, the trains themselves were not much newer. Yet these vintage

corridors were largely what linked the nation, moving it's commerce, keeping

it connected, fed, and supplied. The railroads were one of the first real

monopolies in this country, and travelers were limited to the routes, schedules,

regulations, and limitations imposed by the railroads.

laid down during the days of the frontier, and the wild west; it seemed that

in some cases, the trains themselves were not much newer. Yet these vintage

corridors were largely what linked the nation, moving it's commerce, keeping

it connected, fed, and supplied. The railroads were one of the first real

monopolies in this country, and travelers were limited to the routes, schedules,

regulations, and limitations imposed by the railroads.  distance traveler would need to go from one city to another, seeking the

road in each town which would lead to the next. In order to keep from dead

ending in the middle of nowhere, the wise traveler would generally plan his

route to lead from one major city to another. So the new federal roads were

laid out to follow the cities which preceded them.

distance traveler would need to go from one city to another, seeking the

road in each town which would lead to the next. In order to keep from dead

ending in the middle of nowhere, the wise traveler would generally plan his

route to lead from one major city to another. So the new federal roads were

laid out to follow the cities which preceded them.  There is more to the old road, however, than places

to eat, or stay, and places to buy trinkets. One of the more interesting,

and hopefully enduring, legacies of the old road comes from all of the cities

and towns stretched out across it's length. Some were never anything more

than little stops to eat and get gas (so to speak), while others were large

cities which long predated the existence of the road. All became part of

it's substance, coloring, and flavoring it with their own unique styles,

even as they were colored and flavored by the road. Regions too, added their

share to the allure of Route 66. The Midwest, the Southwest, California,

and bits of the south, all added to the experience of traveling through the

breadth of America on Route 66.

There is more to the old road, however, than places

to eat, or stay, and places to buy trinkets. One of the more interesting,

and hopefully enduring, legacies of the old road comes from all of the cities

and towns stretched out across it's length. Some were never anything more

than little stops to eat and get gas (so to speak), while others were large

cities which long predated the existence of the road. All became part of

it's substance, coloring, and flavoring it with their own unique styles,

even as they were colored and flavored by the road. Regions too, added their

share to the allure of Route 66. The Midwest, the Southwest, California,

and bits of the south, all added to the experience of traveling through the

breadth of America on Route 66.  Some of the high desert mining towns in Arizona, are particularly unique.

Hackberry, and Seligman seem like little more than collections of shacks.

Oatman with it's free ranging wild burros, or Kingman, climbing up the side

of a mountain, surrounded by high desert, and twisted roads, seem somehow

otherworldly. In California, the little hamlets of Amboy, Newberry Springs,

and Bagdad seem to define the notion of the little town in the middle of

nowhere. Set in the heat of the desert, amidst dried out lake beds, there

is no earthly reason for these towns to be here. There is no industry, no

hope of agriculture, and no agreeable climate. The only reason these towns

ever came to be, was the presence, and the need to service, the road.

Some of the high desert mining towns in Arizona, are particularly unique.

Hackberry, and Seligman seem like little more than collections of shacks.

Oatman with it's free ranging wild burros, or Kingman, climbing up the side

of a mountain, surrounded by high desert, and twisted roads, seem somehow

otherworldly. In California, the little hamlets of Amboy, Newberry Springs,

and Bagdad seem to define the notion of the little town in the middle of

nowhere. Set in the heat of the desert, amidst dried out lake beds, there

is no earthly reason for these towns to be here. There is no industry, no

hope of agriculture, and no agreeable climate. The only reason these towns

ever came to be, was the presence, and the need to service, the road.

locals.

locals.  There is a sort of a combination of quaintness, excess,

wholesomeness, and self indulgence that we associate with the bygone days

of the old American Dream. Certainly many other versions of the American

Dream have risen, but there is something special about the post war boom,

optimism, power, and sense of purpose that is longed for, even by those who

helped bring about it's demise. The social activism, sexual revolution, new

politics, and self awareness of the sixties, and seventies toppled much of

the aura of old America. Though few people miss the racism, quiet hypocrisy,

and mild paranoia of those days, our "progress" has not come without a price.

In curing, or trying to cure many of our former social ills, we have unwittingly

discarded much that was of real value to us. It seems like a case of "the

operation was a success but the patient died." The old evils have been replaced

by a set of new ones, less apparent, more complex, and more difficult to

deal with. They have been replaced by the hypocrisy of political correctness,

a distrust of our own government, loss of faith, loss of confidence, and loss

of belief in our own culture and morals.

There is a sort of a combination of quaintness, excess,

wholesomeness, and self indulgence that we associate with the bygone days

of the old American Dream. Certainly many other versions of the American

Dream have risen, but there is something special about the post war boom,

optimism, power, and sense of purpose that is longed for, even by those who

helped bring about it's demise. The social activism, sexual revolution, new

politics, and self awareness of the sixties, and seventies toppled much of

the aura of old America. Though few people miss the racism, quiet hypocrisy,

and mild paranoia of those days, our "progress" has not come without a price.

In curing, or trying to cure many of our former social ills, we have unwittingly

discarded much that was of real value to us. It seems like a case of "the

operation was a success but the patient died." The old evils have been replaced

by a set of new ones, less apparent, more complex, and more difficult to

deal with. They have been replaced by the hypocrisy of political correctness,

a distrust of our own government, loss of faith, loss of confidence, and loss

of belief in our own culture and morals.