Titan Missile Museum

|

|

|

| The Cold War |

The Titan |

The Museum |

| Topside |

The Control Area |

The Missile |

We are looking south, across a desert terrain, which strikes a midwesterner as exotic. The mountains, in the background, are in Mexico. This stark landscape was the home, to the missile fields which held the largest, most powerful, and most powerfully armed ICBM, that America ever deployed. |

||

The Cold War spawned many weapons, and many approaches to defense. One of the more traditional ideas followed, was that of placing one's major forces behind impenetrable fortifications. This strategy goes back to ancient times, to the building of castles or of high city walls. It is an idea which served the armies of many civilizations well, through most of human history; but which was superseded by new developments in the power and mobility of modern weapons systems. Some time before the beginning of the First World War, fixed fortifications became obsolete. Even before this, fixed fortifications would be subject to siege. A siege could sometimes work, by forcing the defenders out, through starvation. The siege army would simply place itself out of range of the weapons of the day, and then wait. A siege might be broken by reinforcements, or by the siege army itself starving; but the walls would generally protect the castle, or fortified town from direct attack. This was a time consuming, process, which, though not overtly violent, was definitely a test of the nerves of both sides.

The siege was a strategy which was based upon the inability of the defenders to reach the attackers, and of the attackers inability to breach the fortifications of the defenders. It was roughly a stalemate, with neither side daring to attack the other. It was, all other things being equal, a test of wills. The victor would be the side which had the will, or the means, to hold out the longest. Eventually, canon, and then modern artillery, along with the tank, and the airplane were to make fixed fortifications useless. The key to the new modern battlefield was mobility. Armies continually maneuvered, and attempted to flank each other, the way that a pair of boxers might circle and spar. This new mode of warfare was quick, and dynamic. Unlike wars of the past, which might last for years, decades, or even generations, modern wars would last for weeks, or months. Only in the most extreme case, as in the two world wars, would a modern war be an extended trial. This, too, was about to change, with the coming of the nuclear age, and the advent of The Cold War.

The cold war seemed a very strange way of fighting, to modern tacticians; but would have been a familiar strategy to ancient generals. The Cold War was a siege. Neither side dared to attack the other, so each settled in, armed themselves, and awaited any sign of weakness from the other. Like the siege of old, a cold war is not overtly violent; but the threat of violence was always there, pent up and awaiting the first sign of weakness. In ancient times, a besieging army which dared to attack, would soon find itself destroyed. The same held true in the nuclear age. The hardened silos of the modern ICBM seem a fitting counterpart for the castle of old. There were also submarines, and bombers, armed with nuclear weapons; but these could be hunted down, and destroyed, once their locations were known. The ICBM, sitting in it's hardened silo, in the middle of foreign territory, and sometimes in concert with ABM systems was, like the old time castle, a much tougher nut to crack. They were designed, from the outset, to survive a nuclear attack.

In addition to the hardness of the sites, there was also the quickness of the response time. Though the first generation of cryogenically fueled missiles had long response times (as much as four hours), and needed to be raised from their silos for launch, the newer versions could be out of their silos in minutes. What this meant for the enemy was that even if there was doubt about the hardened sites' survivability, the missiles could be out if their silos before a first strike could even arrive. As in the old days of the castle, and fortified town, the new nuclear delivery systems guaranteed certain destruction to the attacker. So definite was the certainty of the accurate delivery of warheads, and the near impossibility of defending against them that, after the mid sixties, no attempts were even made at anti missile defense. Instead, it was to be the certainty of destruction, which would be the shield against attack. The official military doctrine was labeled MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction). This spawned the era of Cold War paranoia, Duck and Cover, civil defense, and the emergence of what Eisenhower had called the Military Industrial Complex.

The United States deployed four major, land based ICBM systems, since the invention of the concept. They are the Atlas, Titan, Minuteman, and MX. Of the four, only the Minuteman, and MX are in present deployment. The currently deployed systems both use solid fuel rockets, as opposed to the liquid fuel systems of the original Atlas, and Titan systems. The Atlas, as well as the earlier versions of the Titan, used cryogenic fuels, which is to say, they used liquefied gas, liquid oxygen, as an oxidizer. This enormously complicated handling and readying procedures, and gave the Atlas a four hour launch time.

Their earlier development, and their retirement as deployed weapons, might lead the reader to believe that the liquid fueled rocket is inferior to the solid fueled type; but this is not necessarily true. Each type has it's own advantages. What has happened, is that America has decided to emphasize safety, longevity, and ease of maintenance, over power, and range. Solid fuel rockets need very little attention, compared to their liquid fueled counterparts. Where every Titan, and Atlas missile was located at a manned base, the Minuteman, and MX missiles are in unmanned silos, located remotely, and occasionally checked on, by servicers. One of the things which makes this possible is the great advance in nuclear science, achieved in the late fifties, and into the sixties, and beyond. Where the warhead of the Titan weighed 6200 pounds, and the complete re entry package could weigh in the neighborhood of four tons, the W-59 of the Minuteman II weighed 680 pounds, and the W-63 of the modern Minuteman III weighs 253 pounds.

The appropriately named Titan missile is the

largest, and most powerful missile that the United States has ever deployed.

It also carried the largest, most powerful warhead, ever installed on

an American ICBM, the 9 MT W-53. The Titan missile was used to put men

into space, during the Gemini missions. There were 140 Titan II missiles

manufactured. Some were deployed in the ICBM role, and some were used as

trainers, while another dozen were used to launch the ten Gemini space missions

in the sixties. Many were kept as spares, and a few were used to launch

various military payloads into orbit. The first launch of a Titan was in

1959, and the first of the improved Titan II version was in 1963, while the

last was in October of 2005. The missile was retired, as an ICBM, in 1987,

and is now considered obsolete, even for space missions, due to the high

cost of the exotic fuels used. Still, for a missile which was designed for

a ten year service life, the 25 year deployment of the Titan II was pretty

impressive.

The appropriately named Titan missile is the

largest, and most powerful missile that the United States has ever deployed.

It also carried the largest, most powerful warhead, ever installed on

an American ICBM, the 9 MT W-53. The Titan missile was used to put men

into space, during the Gemini missions. There were 140 Titan II missiles

manufactured. Some were deployed in the ICBM role, and some were used as

trainers, while another dozen were used to launch the ten Gemini space missions

in the sixties. Many were kept as spares, and a few were used to launch

various military payloads into orbit. The first launch of a Titan was in

1959, and the first of the improved Titan II version was in 1963, while the

last was in October of 2005. The missile was retired, as an ICBM, in 1987,

and is now considered obsolete, even for space missions, due to the high

cost of the exotic fuels used. Still, for a missile which was designed for

a ten year service life, the 25 year deployment of the Titan II was pretty

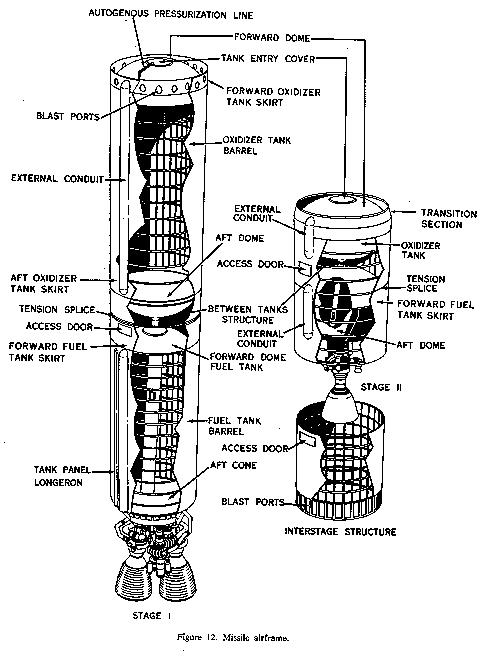

impressive.The original Titan missiles were developed in tandem with the Atlas missile. As these were the first ICBM missiles developed by the United States, it was thought to be a good idea to have two separate development programs, using two different approaches at design. The Atlas was the lighter, smaller, and cheaper version. It was essentially, a flying fuel bladder. There was no framing in the Atlas, and it depended upon the pressure of the internal fuel, to hold it's shape. An empty Atlas missile would go limp, like an empty balloon. The Titan was a stronger, heavier, and more expensive design. It was able to carry larger warheads, and carry them farther than the Atlas. The Titan also had two stages, compared to the single stage (some call it a stage and a half, because of the partial engine shutdown, once in space) of the Atlas. The Atlas was a liquid fueled rocket, which used a cryogenic oxidizer, as was the original version of the Titan. Cryogenic fuels are dangerous, difficult to handle, and their use gives a missile a long pre launch period. The Atlas was retired, as an ICBM, in 1965.

The Titan II, was designed to use nitrogen tetroxide, rather than liquid oxygen as an oxidizer. It used Aerozine 50, as it's fuel. These two chemicals are hypergolic, which is to say that they will ignite instantly, upon exposure to each other. Because of this, careful handling is required; but even this combination is far less dangerous than the use of liquid oxygen. It also has the virtue of not imposing the requirement for cryogenic handling. Though nitrogen tetroxide is extremely expensive, the instance of several spectacular accidents in missiles using cryogenic fuel, made the comparative cost, in lives and property, rather cheap.

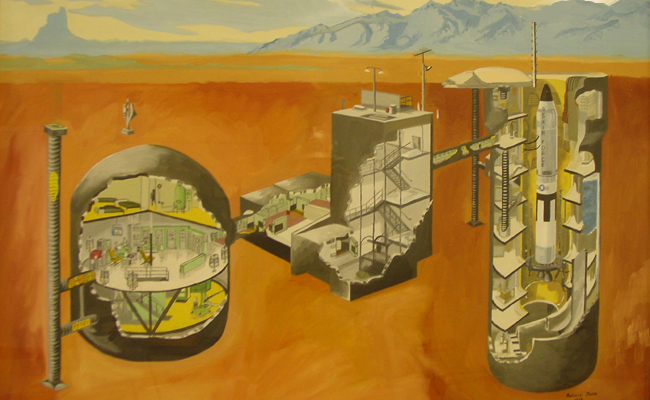

Going to the new fuel permitted the launch sites to be smaller, and less complicated. The original sites required fuel handling rooms, as well as missile erectors. The

9,000 mile range of the Titan II permitted a bit more leeway in dispersal.

Where the Atlas missiles were based in the Midwest, and the Minuteman in

the north, and northwest, the Titan could be deployed anywhere in the country,

and still posses the range to hit targets in the Soviet Union. Liquid oxygen

could not be stored within the missile, and needed to be kept in special

insulated tanks. The missile would be fueled upon the command to launch.

The newer Titan II missiles, once fueled, could remain fueled for the life

of the missile, which greatly reduced launch time. The newer silos were designed

to be flooded with 100,000 gallons of water upon launch, and the silos themselves,

were lined with a series of panels designed to absorb sound and vibration.

These modifications permitted the missiles to be fired directly from their

silos. Previously, the missiles had needed to be raised from their silos,

prior to launch, to prevent them from being damaged by the heat and vibration

of ignition. The original missiles were based in groups of three, with handling

rooms, a power room, and assorted communications and support facilities.

The newer Titan II bases had only an entrance vestibule, a control room with

living spaces above, and the silo itself. The new bases housed single missiles,

rather than groups of three. Titan II missiles were deployed in the Southwest,

some within site of the Mexican border.

9,000 mile range of the Titan II permitted a bit more leeway in dispersal.

Where the Atlas missiles were based in the Midwest, and the Minuteman in

the north, and northwest, the Titan could be deployed anywhere in the country,

and still posses the range to hit targets in the Soviet Union. Liquid oxygen

could not be stored within the missile, and needed to be kept in special

insulated tanks. The missile would be fueled upon the command to launch.

The newer Titan II missiles, once fueled, could remain fueled for the life

of the missile, which greatly reduced launch time. The newer silos were designed

to be flooded with 100,000 gallons of water upon launch, and the silos themselves,

were lined with a series of panels designed to absorb sound and vibration.

These modifications permitted the missiles to be fired directly from their

silos. Previously, the missiles had needed to be raised from their silos,

prior to launch, to prevent them from being damaged by the heat and vibration

of ignition. The original missiles were based in groups of three, with handling

rooms, a power room, and assorted communications and support facilities.

The newer Titan II bases had only an entrance vestibule, a control room with

living spaces above, and the silo itself. The new bases housed single missiles,

rather than groups of three. Titan II missiles were deployed in the Southwest,

some within site of the Mexican border. Titan - Gemini

In common with the Atlas, the Titan was used in

the American space program. The most famous use was as the launch vehicle

for the Gemini manned space missions. These capsules orbited, between

100, and 250 miles above sea level, and held two men. There was a design

version which would have carried between 9 and 12 crew members, and would

have landed using a paraglider. This would have been used for various missions,

satellite deployment, and maintenance, and possible servicing and manning

of a space station. The project was dropped in favor of the Space Shuttle.

Still, we could produce this craft today, with very little lead time, and

there are plenty of Titan missiles around to act as launch vehicles.

In common with the Atlas, the Titan was used in

the American space program. The most famous use was as the launch vehicle

for the Gemini manned space missions. These capsules orbited, between

100, and 250 miles above sea level, and held two men. There was a design

version which would have carried between 9 and 12 crew members, and would

have landed using a paraglider. This would have been used for various missions,

satellite deployment, and maintenance, and possible servicing and manning

of a space station. The project was dropped in favor of the Space Shuttle.

Still, we could produce this craft today, with very little lead time, and

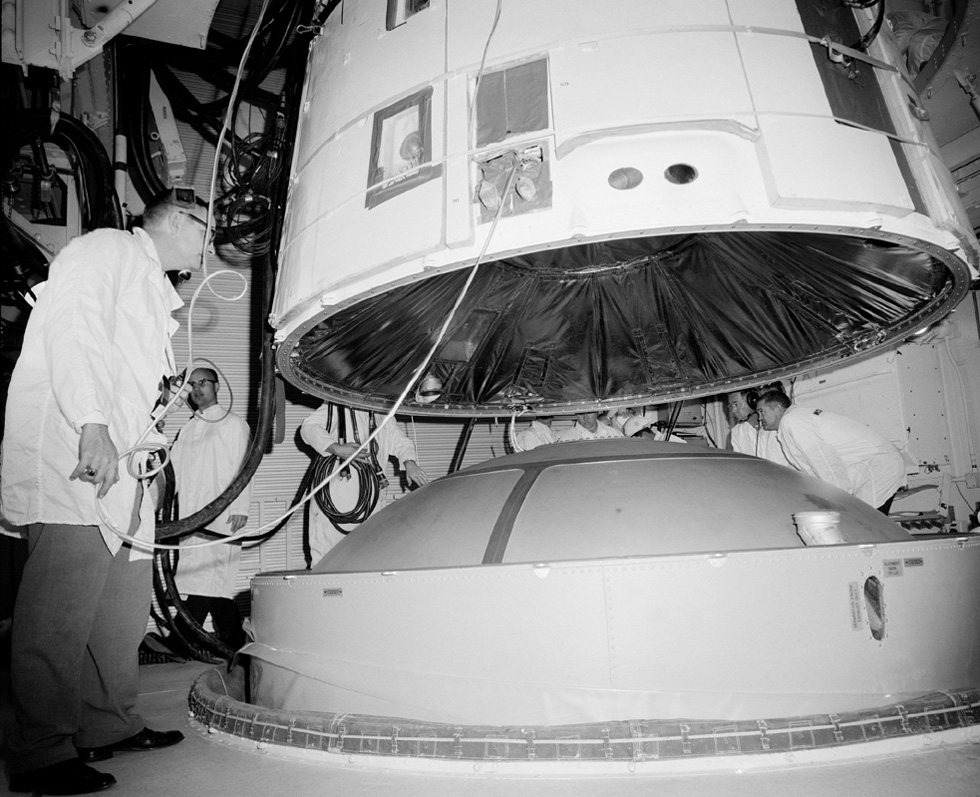

there are plenty of Titan missiles around to act as launch vehicles. The Gemini launch vehicles were little changed, from their ICBM counterparts. The Gemini capsules were designed to fit on the missiles, and to roughly match the MKVI re entry vehicles in regards to weight and size, so that little modification was necessary. Of the twelve missiles used, and the twelve Gemini missions launched, ten were manned, with the first two being unmanned test platforms to verify safety. The Gemini's were used as training platforms for the future explorers of the moon. The project was started after the Apollo project, and in many ways the Gemini capsules were more advanced, and had more potential. Gemini moon missions were proposed.

The Titan - Gemini partnership, is a good example of how military technology can be adapted for peacetime use. Without the military missile and ICBM programs, it might have taken 50 years or more to get into space, and on to the moon. The money would not have been there; but more importantly, the knowledge, and the pool of experienced workers would have been nowhere to be found. If the Space Race, of the sixties gave the United States a huge technological lead over everyone else, then the development of military technology made the Space race possible.

Below is a photo of technicians installing a Gemini capsule onto a Titan II missile.

The Titan museum is located about 25

miles south of Tucson Arizona, in a desert area, very near the Mexican

border. It is the only remaining, intact, Titan missile base. The others

were destroyed, or at any rate, made unusable. Unlike the Minuteman NHS, The Titan Missile Museum is all at one

location. There are, essentially, three sections. There is the museum,

with exhibits, a short lecture, and a film, there is the above ground portion,

with some vehicles, rocket engines, fueling equipment, and the antennas

and original entrance. Then there is the underground base itself, with

the silo, vestibule, and control area.

The Titan museum is located about 25

miles south of Tucson Arizona, in a desert area, very near the Mexican

border. It is the only remaining, intact, Titan missile base. The others

were destroyed, or at any rate, made unusable. Unlike the Minuteman NHS, The Titan Missile Museum is all at one

location. There are, essentially, three sections. There is the museum,

with exhibits, a short lecture, and a film, there is the above ground portion,

with some vehicles, rocket engines, fueling equipment, and the antennas

and original entrance. Then there is the underground base itself, with

the silo, vestibule, and control area. Long before it was a museum, this was missile site 571-7, of the 571st Strategic Missile Squadron, 390th Strategic Missile Wing. This silo went on alert in July of 1963, and was taken off of alert in November of 1982, as a part of a scheduled retirement of all Titan missiles by 1987. After decommissioning, most of the 54 active silos were subject to salvage, and then destruction. Three thousand pounds of explosive were used to destroy the framing for the silo door, after which the site was left exposed to satellite inspection for six months. So heavy and well fortified were the silo doors, that there was not even an attempt made to remove them. Instead, the silo door was welded shut. The site was then sealed, backfilled, and graded. Still, so heavily built were these structures, that they were essentially left intact, if filled.

The museum is open every day except Christmas, and Thanksgiving. The basic tour is available every day, includes the control room, as well as the main level of the silo, and is led by a pair of guides, after the viewing of a short video. On tuesdays, as well as during certain special occasions, there are more extensive tours, covering the whole of the complex. The $8.50 admission is quite reasonable, particularly considering the obvious costs of upkeep, and the length of the tours. A one hour guided tour is part of the ticket price. More extensive tour are available, generally on Tuesdays, and on the first Saturday of the month. There are also occasional field trips to other, nearby silos, which have been long abandoned. The Titan Missile Museum is associated with the Pima Air and Space Museum, and combination tickets are available.

A significant above ground structure was added by the museum, after it took the site over. This houses administration, the lecture room, a gift shop, and some exhibits. This is where visitors pay their admission, look around, and are gathered to be taken outside, and then underground, for guided tours. You could spend quite a while wandering through the various items on display. There is a re entry vehicle on display, as well as models of various strategic missiles. Books, videos, and various trinkets are on sale, including some unique items, like actual pieces of rebar, salvaged from decommissioned Titan sites.

After viewing a video, recapping the history of the Titan, and of the Cold War, visitors are issued hard hats. The guides warn that there are stairs, and advise that an elevator is available. A pair of guides accompanied us on the one hour tour. They know the site, and are there to share their knowledge, and to keep visitors on schedule, since many tours are taken through each day. They are friendly, knowledgeable, and seem to have a real enthusiasm for what they do. In addition to keeping tourists from falling behind, or getting lost, they operate the elevator, for those who can not take the stairs. They also insure that people stay out of the closed off areas of the site.

We had a much easier time, on our visit. We passed a number of phones on our way down. The stairway down was posted with warnings about rattlesnakes, and reminded me a bit of the entrance to a rural storm cellar. After several flights of stairs, the vestibule opens up into a large entryway, with a large steel and concrete blast door, looking like the door to a bank vault.

The guides took us through the control room, and enacted a launch sequence. We were also taken down a long hallway, called the cableway, which connected the silo to the control area. Everything is shock mounted, suspended on huge springs contained in rather large drums. This would allow the whole facility to bounce a bit, during a nearby nuclear hit, rather than transmitting the shock to any gear which might be damaged.

These bases were designed to house crews for extended shifts, and were built with complete kitchen, bathroom, and sleeping facilities. The extended tours, given on tuesdays, take the visitor through all of these areas. Were the unthinkable to ever happen, the crews were to remain below, awaiting orders, or more likely, destruction by incoming missiles. The latter designs, such as the Minuteman, were designed to be much smaller, and much less elaborate. As weapons designers became more skilled at their craft, designed smaller warheads, and more compact missile designs, which required less attention, there was no need for such large underground facilities. With the advent of the modern, smaller ICBM, as well as the use of strategic missile submarines, the Titan bases are likely to be the last of their kind.

Click on the links below, for a photographic

tour

| Topside |

Going Underground |

The Missile |