The Helical Feed Magazine (9mm)

This is informative and , in it's own way, rather interesting reading, but it is a bit dry, and perhaps more detailed than the casual reader might want. The patent is a general description of the workings of the magazine, and it may be noted that the patent covers the use of this design for cartridges, as well as paint balls.

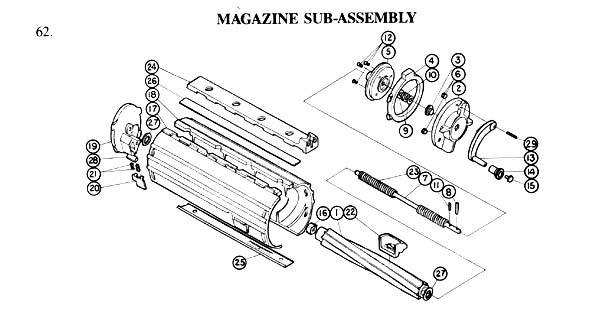

These magazines are constructed of fiberglass reinforced plastic, will

not rust, and are surprisingly light and sturdy. The magazines may be stored

loaded without shortening the life of the magazine spring, by releasing the

spring tension. Disassembly is fairly simple, though the magazines should

rarely need cleaning. The above diagram would seem to suggest that taking

these magazines apart is is a non-trivial task, and that those wishing to

avoid disaster might want to give this a second thought. Loading may be accomplished

by simply inserting the cartridges one by one, or through the use of a special

crank wound tool sold for rapid reloading. There is a winding crank with

a folding handle located at the rear of the magazine housing. It may be necessary

to turn the crank a couple of times, putting some tension on the spring,

to bring the magazine follower up to the feed lips. Once this is done, the

rounds may be loaded against the slight pressure of the follower. As the tension

of the spring increases, it may be released by pushing on a small button

located in the center of the winding crank. Once the magazine is completely

loaded, this button may be depressed to completely remove tension from the

spring, for long term storage, while loaded. With the tension completely

removed from the spring, these magazines must be wound like the old Thompson

style drums. The correct tension is:

These magazines are constructed of fiberglass reinforced plastic, will

not rust, and are surprisingly light and sturdy. The magazines may be stored

loaded without shortening the life of the magazine spring, by releasing the

spring tension. Disassembly is fairly simple, though the magazines should

rarely need cleaning. The above diagram would seem to suggest that taking

these magazines apart is is a non-trivial task, and that those wishing to

avoid disaster might want to give this a second thought. Loading may be accomplished

by simply inserting the cartridges one by one, or through the use of a special

crank wound tool sold for rapid reloading. There is a winding crank with

a folding handle located at the rear of the magazine housing. It may be necessary

to turn the crank a couple of times, putting some tension on the spring,

to bring the magazine follower up to the feed lips. Once this is done, the

rounds may be loaded against the slight pressure of the follower. As the tension

of the spring increases, it may be released by pushing on a small button

located in the center of the winding crank. Once the magazine is completely

loaded, this button may be depressed to completely remove tension from the

spring, for long term storage, while loaded. With the tension completely

removed from the spring, these magazines must be wound like the old Thompson

style drums. The correct tension is:

50 Round

Magazine 10 Turns of the

crank

100

Round Magazine 23 Turns of the

crank

It is important to remember to release the tension on the spring, before

turning the crank, to prevent over winding. The spring is said to be very

strong, and the company claims that some slight over winding will not seriously

damage the magazine, but with the prices of Calico magazines being what they

are, this is not a risk I would take lightly. The top of the magazine is equipped

with a number of circular windows which are marked with the numbers of rounds

remaining; very handy. Shown above, is a side by side view of the 50 and

100 round magazines. The sights are plainly visible at the rear of the fifty

rounder, and about halfway back on the top of the hundred rounder. The brass

showing through the circular indicator windows in the examples, shows that

both mags are completely loaded.

Unloading the magazine is a simple procedure, thanks

to the spring loaded magazine lips. These are metal inserts which may be pushed

back, within the plastic magazine housing. In addition to being an aid in

emptying the magazines, these retractable feed lips make the use of a rapid

reloader possible. The reloader will be more thoroughly covered in the accessory

section, but suffice it to say, this is a real time and finger saver. It

holds fifty rounds, is of plastic construction (of course), and presently

sells for about $60

As of this writing, these magazines are selling

for $200-$300 in the fifty round version, and about $100 more for the larger

model. In the early nineties, when I bought my Calicos, these magazines retailed

for $49 (50 rounds), and $59 (100 rounds). They could be bought through

distributors, and mail order companies for about $10-$15 less. Oh for the

good old days. They are available today from some of the distributors listed

in my links section, though supply is sharply limited, and the scarcity

of the mags can make finding a dependable supplier a matter of luck. The

police and military only mags, produced today, sell for about $70-$100 each,

and are the only magazines Calico presently offers. Whatever their remaining

stock of civilian magazines might be, it is being held in reserve for inclusion

with with new guns still being sold. Once this stock of magazines runs out,

Calico will no longer be able to sell it's line of firearms to civilians.

Needless to say, the gun bill of 1994, is all but killing the civilian Calico.

There would be little point in Calico producing a 10 round version of this

magazine for a new generation of post ban guns, though I have seen post ban,

10 round versions of the Thompson drum magazine, available for those who

want the look of the classic "Tommy gun". The Calico does not have the history

of the Thompson, and there would be little call for a civilian version with

a "dummy" 10 round magazine. Thompson fifty rounders are now selling for

almost $700, making the fifty, and one hundred round Calico mags seem like

quite a bargain.

mags. I have yet to clean mine, after years of service, and they still

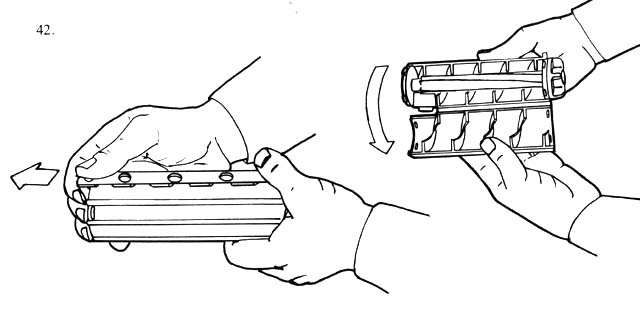

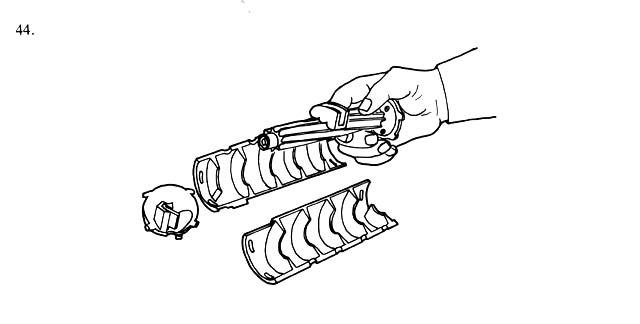

function flawlessly. The magazine body is of two pieces. Sliding the top

molding off of the magazine body permits the separation of the two halves.

The magazine should be unloaded, and all tension should be released from

the magazine spring before this is attempted. Once opened, the magazine separates

into a few simple subassemblies which may be cleaned and very lightly lubricated.

All of these diagrams are taken from the manual, and the procedures laid

out there are pretty straight forward. I would caution against the sin of

over lubricating, something that I am often guilty of myself, as this will

be likely to enhance the formation of sludge, and plain old gunk within the

body of the mags. A drop or two of Triflon or Break Free around the spring

should be sufficient.

mags. I have yet to clean mine, after years of service, and they still

function flawlessly. The magazine body is of two pieces. Sliding the top

molding off of the magazine body permits the separation of the two halves.

The magazine should be unloaded, and all tension should be released from

the magazine spring before this is attempted. Once opened, the magazine separates

into a few simple subassemblies which may be cleaned and very lightly lubricated.

All of these diagrams are taken from the manual, and the procedures laid

out there are pretty straight forward. I would caution against the sin of

over lubricating, something that I am often guilty of myself, as this will

be likely to enhance the formation of sludge, and plain old gunk within the

body of the mags. A drop or two of Triflon or Break Free around the spring

should be sufficient. If the worst should happen, and you damage your magazine, or it wears out, there is a repair service affiliated with the "unofficial Calico web page" given in my links. As of this writing, the charge is $30 plus the cost of shipping and parts. This will likely put the total cost at around $50-$100, cheap compared to the cost of replacement magazines, when they can be found. Parts are still available from Calico, though they will no longer sell a civilian one of their magazines.

There are magazine repair kits available for the adventurous (or the cheapskate,

who does not wish to part with an extra $30) The repair kits contain the

internal workings of the magazines. There is also an outer shell kit, which

contains the external parts. So restrictive are the provisions of the magazine

ban, that these parts must not be shipped, or even stored, together. Doing

so would constitute a contraband magazine in the eyes of the B.A.T.F. The

total cost of the parts required to construct a 100 round magazine would be

around $170. This cost does not include legal fees, the cost of your confiscated

gun collection, and jail time, if you are ever caught with it. Possession

of all of these parts, assembled or not, would also make you a felon, and

would prevent you from ever legally owning a gun again. If only real crime

were taken this seriously, and actual criminals treated this harshly. This

situation will end in 2004, unless the powers that be vote the ban into

permanence. In the meantime treat these magazines as if they are gold; ounce

for ounce they are about as valuable.

There are magazine repair kits available for the adventurous (or the cheapskate,

who does not wish to part with an extra $30) The repair kits contain the

internal workings of the magazines. There is also an outer shell kit, which

contains the external parts. So restrictive are the provisions of the magazine

ban, that these parts must not be shipped, or even stored, together. Doing

so would constitute a contraband magazine in the eyes of the B.A.T.F. The

total cost of the parts required to construct a 100 round magazine would be

around $170. This cost does not include legal fees, the cost of your confiscated

gun collection, and jail time, if you are ever caught with it. Possession

of all of these parts, assembled or not, would also make you a felon, and

would prevent you from ever legally owning a gun again. If only real crime

were taken this seriously, and actual criminals treated this harshly. This

situation will end in 2004, unless the powers that be vote the ban into

permanence. In the meantime treat these magazines as if they are gold; ounce

for ounce they are about as valuable.

The photo shows a modification of the original snail shell magazine, made for use with the AK-47 series of assault rifles. It is shown in company with the 50 and the 100 round versions of the Calico magazines, for size comparison. The AK drum holds 75 rounds, and it can be seen that it is much larger than the Calico mags. I can personally vouch for the fact that it is also much heavier, and, despite it's weight, much more delicate. These AK mags are a direct development of the Soviet PPSH mag, one of which is shown with it's cover removed, in the next photo. There is a variation of the AK drum magazine which will fit on an M-16 rifle, and has been modified to feed the .223 round. All of these drums owe their design to the 32 round "snail shell" magazine in 9mm, for the Luger pistol. This was a development for World War One, and was an attempt to give the

trench bound soldier greater firepower in a smaller package. tactically,

this was the precursor to the submachine gun. This same magazine was used

on the German MP 18 submachine gun, though it was later replaced with a

more conventional box type magazine. The 9x19 round of the Calico, and the

7x39mm round of the AK are also shown for comparison.

trench bound soldier greater firepower in a smaller package. tactically,

this was the precursor to the submachine gun. This same magazine was used

on the German MP 18 submachine gun, though it was later replaced with a

more conventional box type magazine. The 9x19 round of the Calico, and the

7x39mm round of the AK are also shown for comparison. The drum mag of the Thompson works on similar principles, but is modified somewhat. The Thompson drum has no feeder column, and so can only be fired in the 1928 model Thompson, and others designed specifically for it. These weapons do not have magazine wells in the traditional sense, but use a cut out in the frame instead, with multiple locking lugs for the magazine instead of a single catch. The Thompson drum will not fit on the later "M-1" Thompsons produced for use during World War Two, because this model lacks the cut out in the frame. Drums for the Thompson were typically of the 50 round capacity, though there was a large, heavy, and cumbersome version which held 100 rounds available.

In addition to the "true" drum magazines, a number of drum style magazines have been produced. The more common versions of these tend to be simple ammunition carriers, rather than actual magazines. These ammunition carriers function as storage boxes for belts on belt fed guns. Guns using these systems, generally feed from the bottom, in the fashion of a magazine fed weapon, rather than from the side, which is the more common method used by belt fed weapons. The old Stoner system, along with the Soviet RPK light machine gun used "magazines" of this type. The other type of "drum style" magazine is actually a standard box magazine which has been curved sideways into a complete circle. The only advantage to this type of magazine is that it does not protrude as far from the magazine well as a straight version would. I am aware of only one example of this type of magazine. It was produced for the AR-15/M-16 series of rifles, and was of molded plastic.

Compared to the simple elegance of the helical design used in the Calico magazines, the other drums seem quite primitive, and crude. These other magazines are also considerably more complicated, and delicate internally. They are also all, much harder to load, needing to be opened for loading, and then loaded in stages. The Calico magazines, particularly with the addition of the rapid loading tool, are quite simple to charge. In addition, the more traditional drums are heavy, and their stamped metal bodies are easily dented, and damaged, and susceptible to the effects of corrosion.