The .45 Automatic

Max Pressure 19,900cup/22000psi (standard)

23,000cup

(+P) *

28,000+cup ? (.45

Super)**

38,000 cup

(.460 Rowlan)***

This is considered by myself and many gun experts to be

the ideal defensive handgun cartridge. Even those who tout other cartridges

do not deny the power and reliability of the classic .45 A.C.P. The perceived

flaws and weaknesses of this fine cartridge, are a matter of dispute, and

in any event, have recently been remedied. The dispute centers around what

the purpose of a hand gun should be, and how powerful it needs to be in order

to fulfill this purpose. The generally accepted purpose of a handgun is for

defense. It needs to be small and light enough to be carried comfortably

at all times, concealed if necessary, and it needs to be quick to bring into

action. It also needs to be powerful enough to stop an attacker as quickly

as possible. We tend to have an attitude, these days, that more, bigger,

faster is better, but in some cases this is not true.

The most powerful handgun in the world, is likely the

Thompson Contender with a barrel chambered in one of

the many rifle calibers available for it. This would make a poor defense

gun, though it is an excellent hunting tool. The hunter stalks his prey,

and chooses the time and place of the encounter, ideally killing with one

shot. In a defensive situation, YOU are the prey, and where the aggressor

has had time to plan out his actions, you must react quickly, and decisively.

This requires a gun of a certain size and weight. This combination of requirements,

the need to hit fast, and the need to hit hard, requires some trade offs.

A .44 magnum hits very hard indeed, but the recoil is so intense that you

had better hit your target with the first shot; by the time you are ready

for a second shot you may be hit several times by an opponents less powerful,

but faster firing gun. On the other hand you can pop off .22 rounds and keep

the gun on target as long as you like, but the .22 is not exactly known as

a fight stopper. The .45 fires a large heavy projectile, and it fires it

at a high enough velocity to penetrate and do lethal damage. At the same

time, it is not so powerful that a reasonably well trained person can not

control it in rapid fire. The gun is tried and true, and the section on bullet

lethality will go into more detail about the trade offs made and the results

achieved.

The few perceived shortcomings of the .45

Auto round have been addressed in the last decade or so. One of them is the

chamber pressure limit which keeps the 230 grain bullet in the 800 to 900

fps range. I do not particularly consider this to be a handicap, but for

those who do, there is the fully supported chamber, and the .45 Super round,

along with some others. The fully supported chamber eliminates the major

weakness of the original design which left a small section of brass exposed

near the base of the cartridge, If pressure limits were exceeded, the case

could burst. This is not quite so threatening as a blown cylinder in a revolver,

but a burst case, venting hot gasses down into a magazine full of live cartridges,

is no joke, particularly when the shooters' hand is wrapped around them.

There is also some new brass out there. You can buy .45 +P brass now, which

I imagine is stronger than standard .45 brass. There is also the new .45

Super brass, and ammunition.

The other perceived handicap of the gun was

not really a consideration until the seventies, or possibly the late sixties.

The new generation of "Wonder Nines" were nine millimeter autos with double

column magazines which could hold twice as many rounds as the .45's seven.

This was not a factor earlier because prior to the early seventies there

was only one pistol which was so designed, and that was the Browning P-35,

also known as the Hi-Power. The gun was expensive, and most shooters thought

it better to have 7+1 rounds of a proven, and effective manstopper than the

Brownings' 13+1 in a less effective cartridge.

In the fifties, the government announced a competition

for a new 9mm service pistol to replace the aging stock of "old ugly" M1911

.45 autos. It was also announced that the new pistol should be somewhat

lighter than the old model it was replacing. Colt's response was to rechamber

the classic M1911 for 9mm, and to shorten the gun a bit. Smith and Wesson

responded by introducing the M-39. The M-39 was a double action 9mm, with

an alloy frame. The government changed it's mind, keeping the old Colt

.45 auto for another three decades, and the contract was never filled. The

M-39 was offered to civilians and to police departments, and developed a

certain following. The double action trigger had previously only been available

on much more expensive guns, as had the use of an alloy frame. In 1973, the

gun was modified by widening the magazine well for use of a double column

mag, and was introduced as the M-59, the first of a long line of affordable

double column "Wonder Nines" which they are still producing. Other manufacturers

followed suit, and soon you did not have to be rich to own a double column

gun.

There were also some tests conducted, at about this same

time, which on paper "proved" that the 9mm, in its' lighter, higher velocity

loadings was a better cartridge than the "old, slow" .45. These tests have

since been discredited, and are covered in more detail in the bullet lethality

section. Even for those who still cling to these discredited tests, there

is the fact that, as mentioned above, the .45 can now exceed the velocity

of the 9mm with new brass and supported chamber guns. The so called magazine

capacity deficiency has also been taken care of by Glock, Para Ordinance,

H&K, and some other companies which now make .45 pistols with double

column magazines which hold from 12 to 15 rounds. I have two carbines, the

Mech-Tech, and the Marlin Camp Gun which fire this round. I also have several

pistols, the Glock 21, Para Ordinance P-12, Para Ordinance P-14, the

S&W M-1917, H&K USP,

and the Colt Gold Cup. If you can not help yourself,

you can find out about the .45 Super from a real expert: Ace Hindeman. He produces guns, spring

kits, modification kits, and has worked up safe loads for the caliber. He

is in my list of gun links.

Developments of the .45 Auto

The fully supported chamber has addressed, somewhat, the

major shortcomings of the old .45, and has encouraged experimentation with,

and development of the cartridge. This is very reminiscent of the work done

on the .38 Special in the 1920's, and the .44 Special in the 1950's. These

developments led to the .357, and .44 magnums. These older magnums are all

revolver rounds, and will still fire the less powerful cartridges from which

they were developed. There are three presently produced cartridges which

could be thought of as improved versions of the classic .45. The first is

the +P version of the cartridge, which is a bit less forgiving of some of

the older or weaker pistols out there, and is essentially a standard .45

loaded to reflect the newer, stronger guns being produced today. There is

also the .45 Super, which can be used in a standard .45 Auto, or at any rate,

can be made to chamber in one. Then there is the newest member of the .45

Auto club, the .460 Rowlan.

The .45 Super requires, besides a barrel up to the job,

replacing the stock recoil springs. I have to admit that My large Para ordinance,

is resprung, but really the .45 as it is, almost ideally suits the role of

defensive pistol. Unlike the old revolver based magnums, the .45 Super is

dimensionally the same as it's parent round, and will chamber in standard

guns so caution must be exercised to prevent these higher powered cartridges

from being fired in guns not up to them. The new .45 Super, and +P loads

begin to enter into .44 Magnum territory, and begin to present many of the

problems of that round. The main problem is that of control. A round which

generates enough power to push a pistol half way to the sky can not produce

a very high rate of fire. The flash and report of such a gun inches from

the shooters face does not enhance the accuracy of fire. There is also the

discomfort factor which will tend to insure that a gun this unpleasant to

fire does not get practiced with very often. The power of the .45 in it's

standard loads is low enough so that a pistol of reasonable size and weight

may fire it. Cartridges in the .44 Magnum range are always chambered in large,

and rather heavy guns. I own a .44 mag Ruger Redhawk, and I like the gun,

but would never consider carrying it as a defense gun; it is just too bulky

and heavy.

The .460 Rowlan is a new development, and is somewhat compatible

with the standard .45. Like the older, revolver based magnums, this cartridge

uses a case lengthened somewhat over that of the parent round. Unlike the

older, revolver based magnum cartridges, the parent rounds do not work well

in the magnum guns. There are a couple of reasons for this, and both relate

to the differences in the method of operation between revolvers, and automatics.

Automatics can be very sensitive to the ammunition they digest. They can

also be affected by very small differences in case and round length. The

revolver does not have these handicaps, because the chambers are loaded by

the shooter, and the mechanism is powered by the shooters finger on the trigger.

A round which is overpowered can batter an automatic's slide against it's

frame. A round which is underpowered may not be able to work the slide. The

ammunition actually becomes part of the mechanism of the gun. Some autos

are so sensitive, that the may fail to feed or eject if the shooter holds

them improperly. It is necessary for the springs and surfaces of an automatic

to be much more attuned to the ammunition used in them, than is the case

for a revolver.

The other problem with an automatic has to do with using

cartridges of different lengths. The ammunition used in an automatic

is rimless, and must headspace on the mouth of the case. In practice, auto

rounds are made to headspace by the extractor. This makes an automatic much

more sensitive to the dimensions of the cartridges used. This is a problem

unique to the Rowlan cartridge because, previously, no attempt had been made

to fire cartridges of different lengths in an automatic (there are some who

might feel the need to remind me of the 9x18 cartridges, and of some experiments

with the .380 in the Makarov, but these weapons only worked dependably with

one cartridge, and their failure in the market was a reflection of this).

A revolver has a slight gap between the cylinder and the barrel. The chamber

end of the barrel is widened slightly, and unrifled. This section of the

barrel is known as the forcing cone, and it tapers into the rifling, acting

as a guide for the bullet after it leaves the chamber of the cylinder, thus

the length of the round is not of critical importance in a revolver.

The chamber of an automatic is integral with it's barrel. In a perfectly

headspaced automatic, the slug will just about be touching the rifling. In

this constricted environment, there is no need for a forcing cone, and no

practical way to include one. A widening of the area in front of the chamber

to produce a forcing cone would adversely affect both the strength and accuracy

of the barrel. In a barrel chambered for a .460 Rowlan, the use of a standard

.45 cartridge would require the bullet to cross a gap in the chamber before

striking the rifling. This would adversely affect accuracy somewhat, since

there would be no forcing cone to guide the bullet onto the rifling.

The .45 Super would likely be my first choice for those

who are infected with "power disease" and who don't hear magic in the word

"magnum". This round does not have the power of the .460 Rowlan, as can be

seen on the table below, but it is still well within magnum territory. The

trade off is one between power and flexibility. The .45 Super loses about

100-200 fps to the .460. What it gives back is the ability to use standard

.45 A.C.P. ammunition. Externally, the case is dimensioned exactly as the

standard .45. Internally, it is quite a bit stronger, particularly at the

base. This is not a criticism of the Rowlan; it is a fine cartridge. I consider

the Rowlan to be a great hunting cartridge, but it's lack of true interchangability

with the old .45 A.C.P. would, to my mind, make it a cartridge unique

to itself, rather than an extension of the .45 A.C.P. The exception to this

rule would bee the new Dan Wesson revolvers chambered for the Rowlan. These

guns should be able to fire the .45 A.C.P., the Rowlan, using half moon,

or full moon clips, and probably the .45 Long Colt as well.

Listed below are some of the standard loads to be found

in the various incarnations of the .45 auto. Some loads will not work in

some guns. The .45 Rowlan will not chamber in a standard .45 auto barrel,

though a standard .45 will chamber in a .460 Rowlan barrel. A standard .45

will not have the energy to work the spring of a .460 Rowlan. The .45 Super

will chamber in anything, and should have the power to work a spring in a

.460 Rowlan pistol. The .45 Super should only be used in pistols modified

for it's use, with the exception of the H&K USP, and certain models of

the 1911 from Springfield Armory, which will fire them without modification.

Going in the other direction, Glock has developed

a new shortened version of the 45 called the 45 GAP. The main difference

between the GAP, and the standard cartridge is the shorter length and somewhat

different internal structure of the GAP. You can not simply cut down a standard

45 to make it into a GAP. The GAP also uses small pistol primers rather than

the large ones of the standard 45. All differences aside, what is remarkable

about the 45 GAP, and the 45 ACP are the similarities. The GAP takes advantage

of today's stronger fully chambered guns, and better powders to make the

shorter cartridge perform identically to the longer standard cartridge. Browning

did the same thing at the turn of the last century with the development of

the 45 ACP, which duplicated the ballistics of the much larger 45 LC. What

this means for shooters, is a smaller gun which can still pack the punch

of the full sized 45.

The case length of the GAP is the same as that of the

9mm (19mm, or .775 inches), though the loaded round itself is actually slightly

shorter at 1.07 inches.

Some loads

| Bullet |

Powder |

Measure |

Velocity |

Energy |

| 185gr .45 A.C.P. |

Bullseye |

5.3gr |

914fps |

343fp |

| 230gr .45 A.C.P. |

Bullseye |

4.6gr |

850fps |

396fp |

| 185gr .45 Super |

no load found |

no load found |

1400fps |

805fp |

| 230gr .45 Super |

no load found |

no load found |

1200fps |

736fp |

| 185gr .460 Rowlan |

#7 |

18.5gr |

1530fps |

962fp |

| 230gr .460 Rowlan |

#7 |

15.8gr |

1339fps |

916fp |

*the higher pressures shown are for suitable firearms with

fully supported chambers only

**The only gun which is listed by the manufacturer to fire

.45 Super rounds without spring and/or barrel mods is the H&K USP

***Specially modified guns only.

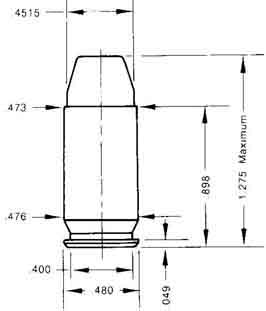

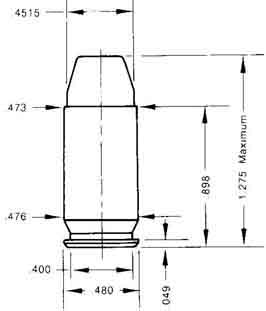

Cartridge dimensions

Cartridge

|

Case Length

|

Case Mouth

|

Overall length

|

Max Pressure

|

Primer

|

45 ACP

|

.898 Inches

|

.473 Inches

|

1.275 Inches

|

22,000cup

|

Large pistol

|

45 Super

|

.898 Inches

|

.473 Inches

|

1.275 Inches

|

29,000cup

|

Large Pistol

|

460 Roland

|

.957 Inches

|

.473 Inches

|

1.275 Inches

|

39,000cup

|

Large Pistol

|

45 GAP

|

.775 Inches

|

.473 Inches

|

1.07 Inches

|

23,000cup

|

Small Pistol

|