|

| The Thompson 1927 |

| Length Overall | Barrel Length | Weight | Caliber | Action Type | Magazine capacity |

| 41 Inches |

16.5 Inches |

13 pounds (w 30 round stick) |

.45 A.C.P. |

Recoil Semi |

10,30,39,50,100 |

| The Legendary

Thompson |

Personal

Observations |

It's

all a Matter of Details |

| Stick

Magazines |

Installing

The Thompson Drum |

Loading

the Drum |

| Thompson

Drums |

Cleaning the

Thompson |

Thompson

Links |

now available with thirty and fifty round magazines. Even so,

with a fifty round drum, which adds another 4.75 pounds to the total

weight, this makes for a very heavy, and rather cumbersome 45 caliber

firearm, by today's standards. Compared to today's Ingrams, AR-15s, AUGs,

and HKs, the Thompson seems to be eminently impractical, not to mention

quite expensive. Still, judging this firearm by it's specs, and by the

performance of it's cartridge, ignores one of the most important fields

by which any civilian firearm is judged; this is the "neat" factor.

If there is one thing that the Thompson has in abundance, its "neat".

now available with thirty and fifty round magazines. Even so,

with a fifty round drum, which adds another 4.75 pounds to the total

weight, this makes for a very heavy, and rather cumbersome 45 caliber

firearm, by today's standards. Compared to today's Ingrams, AR-15s, AUGs,

and HKs, the Thompson seems to be eminently impractical, not to mention

quite expensive. Still, judging this firearm by it's specs, and by the

performance of it's cartridge, ignores one of the most important fields

by which any civilian firearm is judged; this is the "neat" factor.

If there is one thing that the Thompson has in abundance, its "neat".The Thompson has several distinctions, which add greatly to the "neat" factor. The strongest may be the historical factor. Though designed for use in the trenches of the First World War, the gun made it into production too late. Still, it was to have many chances to distinguish itself latter. This was the first American submachine gun, and the first relatively handy fully automatic arm. It was also made famous by numerous television shows, movies, and by it's actual role as a favored weapon of many high profile men on both sides of the law. The infamous Thompson was part of the catalyst which helped pass the odious NFA of 1934, outlawing fully automatic arms for mere subjects of the government. There is also the look of the gun. The vertical grip of the Thompson has been widely copied, and this, along with the drum magazine, and the top mounted cocking lever, give this gun a unique style. Then there is the quality of manufacture.

These guns are wonderfully made, in the classic tradition. A Thompson is a heavy solid gun, made from wood, and machined steel (aluminum versions are now available), finely blued (in the case of the M1927), and well crafted. Compared to the stamped and riveted construction of today's military weapons, the Thompson is a class act. General Thompson designed this gun in a world full of craftsmen and machinists. This rare example of an old world design for the new concept in modern battlefields was relegated into secondary status around the middle of World War Two. Even so, it was a common weapon in Korea, and

was often seen even as late as the Veit Nam War.

was often seen even as late as the Veit Nam War. This particular example is the deluxe 1927 model. This model features a finned barrel, a leaf sight which is adjustable for extreme range, and a Cutts Compensator. This classic version of the Chicago Typewriter also has the horizontal foregrip, and takes the venerable Thompson drum magazine. The original 1927 model was essentially a semi auto version of the famous 1928 model, and fired from an open bolt. The current model has some internal changes, needed to make this gun more difficult to convert to full auto. This is also the model with the top mounted cocking lever, as opposed to having it located on the right side of the receiver as in the M1. The 1927 model is semi auto only, and fires from a closed bolt.

There have been four different design capacities for the famous Thompson drum magazine. All will fit only the 1927,1928 models, but not the latter M1 designs. The first, and most famous, is the venerable 50 round magazine. This was followed by a much larger, and heavier 100 round magazine. This in turn was followed by a 39 round drum. Then there was the sad 10 round magazine, mandated by the useless and unconstitutional magazine ban. These are all classic, first generation style metal drum magazines. They are spring wound, using a removable key, and employing coil springs, and a metal spider to advance the cartridges.

The original fully automatic Thompson submachine guns had 10 to 11.5 inch barrels. Unfortunately, Roosevelt determined (via the NFA of 1934) that we were not to be trusted with short barreled long guns, nor were we to be trusted with fully automatic firearms. So the civilian legal version has a 16.5" barrel. This actually gives it a somewhat more graceful look, as compared to it's stubby war bred brethren. There is probably some small ballistic advantage to the slightly longer barrel, though I suspect it may be very slight. A 230gr bullet which leaves the 5" barrel of a standard 45 pistol at 842 fps, will exit the Thompson's 16.5" barrel at 1092 fps. I would imaging that out of a 10.5" barrel, velocity attainedis on the order of 950 - 1000 fps; but I have no gun with which to test this theory. Auto Ordnance is offering shorter barreled

semi auto guns, for civilian purchase, but these short barreled

guns are covered under the NFA, and must be registered, just like a machine

gun.

semi auto guns, for civilian purchase, but these short barreled

guns are covered under the NFA, and must be registered, just like a machine

gun. The standard civilian legal guns of today also lack the easily detachable stocks of the originals. These guns, in all variations, are quite long, by today's standards, which gives an indication of how remarkable the Uzi, and the rest of the second generation sub machineguns must have seemed at their inception. The chamber of the Thompson is at the point just ahead of the magazine. The magazine, in turn, is forward of the trigger. The spring which drives the bolt, is nearly as long as that of the M-16, and adds about as much length to the rear of the receiver. On the other hand, this lack of space saving features, along with the general excellent production quality of the gun, may be what gives the Thompson it's reputation for dependability. The M-16, M-14, and even the Garrand, all had teething problems of some sort, and required a fair amount of care to keep in working order. The Thompson, except for it's intricate drum magazines, is not quite so fussy.

My first impression, upon handling this gun was "My god, this thing is heavy!" I suspect that this is a common observation. The Thompson is also very bulky, and squared off, compared to today's designs. What is really striking, though, is the huge expanse of finely blued metal. Most guns today are parkerized, have a matte finish, or are largely plastic. The Thompson is blued like an oversized pistol. The use of wood furniture, as opposed to today's plastics, also serves to give the gun a unique look. Though it takes a heavy hand to operate the top mounted cocking lever, this is quite an easy gun to fire. It may be the weight, or the effect of the Cutts Compensator, but recoil is negligible. I have shot some pretty amazing one inch groups with this gun, at 50 yards. What makes these group sizes really amazing is that they are made despite a rather heavy trigger pull. I am hoping for the pull to ease up a bit, once the gun is broken in. The leaf sight is wonderful, and is certainly better than the vestigial little notch. The sight probably adds as much to the gun's great accuracy as anything. Taking this gun to the range is a sure fire ego booster. Everyone wants to look at it, shoot it, own it! This is a feeling I can well understand; I have wanted a genuine Thompson for thirty years.

In case you can't tell, from the length

of this page, or from my comments, I am very enthusiastic about this

gun. I have wanted one since my teens, and like most boys, thought

highly of it as a child. I almost made the purchase several times, in

the last ten years or so, but I could not bring myself to take the

plunge, while the issue of magazine availability was so uncertain. The

costs of these guns skyrocketed, after the ban went into place, but

they eventually returned to Earth. The costs of the magazines was another

matter. A few years into the ban, magazine prices became a bit more reasonable,

at least on the stick magazines. With tens of millions of war surplus

sticks out there, a price drop was inevitable. This was not the case with

the drums. A Thompson drum magazine cost close to $2000, during the first

year or so of the ban. Half way into the ban the price fell to about $1100,

and this was pretty much where it strayed, until a year or so before the

ban was lifted. With Bush in office, and a fair (but by no means absolute)

certainty that the ban would not be renewed, prices dropped to about the

$800 level. Still too much, but getting better. Drum magazines are, at this

writing, selling for about $400, though the ban has now ended. Auto Ordnance

is selling new drums for $284, but is far back ordered. I plan to pick up

a pair of new magazines, as soon as I can get them for under $300. The ban

ended in mid September, and I picked up my new Thompson in early October.

I guess you could say that I figured I had waited long enough.

In case you can't tell, from the length

of this page, or from my comments, I am very enthusiastic about this

gun. I have wanted one since my teens, and like most boys, thought

highly of it as a child. I almost made the purchase several times, in

the last ten years or so, but I could not bring myself to take the

plunge, while the issue of magazine availability was so uncertain. The

costs of these guns skyrocketed, after the ban went into place, but

they eventually returned to Earth. The costs of the magazines was another

matter. A few years into the ban, magazine prices became a bit more reasonable,

at least on the stick magazines. With tens of millions of war surplus

sticks out there, a price drop was inevitable. This was not the case with

the drums. A Thompson drum magazine cost close to $2000, during the first

year or so of the ban. Half way into the ban the price fell to about $1100,

and this was pretty much where it strayed, until a year or so before the

ban was lifted. With Bush in office, and a fair (but by no means absolute)

certainty that the ban would not be renewed, prices dropped to about the

$800 level. Still too much, but getting better. Drum magazines are, at this

writing, selling for about $400, though the ban has now ended. Auto Ordnance

is selling new drums for $284, but is far back ordered. I plan to pick up

a pair of new magazines, as soon as I can get them for under $300. The ban

ended in mid September, and I picked up my new Thompson in early October.

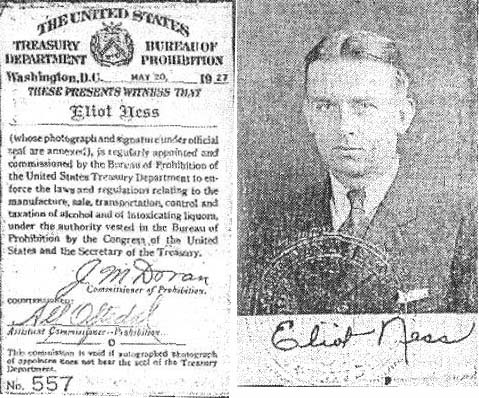

I guess you could say that I figured I had waited long enough.The advertisement to the left, was used in the twenties, and harkened back to an America which had, at the time, only just passed. While the cowboy, indian, rancher, and even the rustler still existed, the days of the wild frontier, open range, and of the Wild West had disappeared thirty years before. Though attempting to associate it with the legend of the expanding frontiers, and independent American, the Thompson would latter become a legend in it's own right. The legend that would surround the Thompson would be, not about war, or about the independent American; but about those who would set themselves as being independent of the law, and of those who would oppose them. The Thompson will always be remembered as the gun of the gangster, and the lawman, rather than that of the rancher, and the trench bound soldier. This ad was placed back in the day when anyone could walk into a hardware store, department store, or sport shop, pick out a Thompson, pay for it, and take it home. This was, I hasten to say, a fully automatic Thompson.

It's hard to justify the purchase of such a gun, by any kind of logic, particularly at the prices these classics are commanding. It sort of reminds me of a firearm version of one of the classic muscle cars of the sixties/seventies, which are now selling for anything from tens of thousands, to millions of dollars. In both cases, you have a machine that is not sophisticated, by today's standards, nor as potent as some of today's top contenders, but there is something reassuring about the classic lines, and performance. Nothing designed today has quite the look or style, and even the performance, still respectable, can sometimes be a bit surprising. It took Detroit thirty years to equal and surpass the performance of the classic muscle cars, and it has never equaled the affordability or exhilaration of those great machines. Much the same can be said of the Thompson. There are still people who argue the merits of the big, heavy Thompson, unsophisticated, and manufactured by forging and milling steel. They compare it to today's stamped, lightweight, sophisticated firearms, and shake their heads. I have read stories of soldiers in Veit Nam carrying Thompsons, and using them to back up their buddies, after malfunctioning M-16 rifles put them in peril. These stories must qualify as the ultimate vindication of a classic design.

Using the

Thompson Stick magazines.

Though these guns are forever associated

with their drum magazines, it has always been far more common to see

a Thompson loaded with a twenty or thirty round stick magazine. This

was particularly true after the introduction of the M1 models, during

the Second World War. These newly designed models, stripped down for

ease of manufacture, were not capable of taking the drum magazines. This

was due, in large part, to the cost of the drum magazines, but weight,

and the relative fragility of the complicated winding mechanisms were

also factors. Millions of M1 Thompsons were manufactured, while the drum

capable 1921, and 1928 models numbered only in the thousands.

Though these guns are forever associated

with their drum magazines, it has always been far more common to see

a Thompson loaded with a twenty or thirty round stick magazine. This

was particularly true after the introduction of the M1 models, during

the Second World War. These newly designed models, stripped down for

ease of manufacture, were not capable of taking the drum magazines. This

was due, in large part, to the cost of the drum magazines, but weight,

and the relative fragility of the complicated winding mechanisms were

also factors. Millions of M1 Thompsons were manufactured, while the drum

capable 1921, and 1928 models numbered only in the thousands.

The drums could also be quite a chore to load, and maintain, and were fairly difficult to install, particularly in the heat of battle. If the small "Third Hand" used to install the drums was lost, installation could be next to impossible. Drums were also susceptible to denting, overwinding (or lack of winding), and could make the already heavy guns really clumsy to handle.

The original Thompson stick magazines had a capacity of 20 rounds; for extended firing, the drum magazine was used. When the military redesigned the Thompson for the Second World War, the drums were not considered to be practical. It was also noted that several additional manufacturing steps were required, to make the guns capable of accepting them. These steps were eliminated from the M1 versions, which served to simplify manufacturing, thus the cut out, and guide slots needed for the drums were deleted from the design. The external magazine latch was also deleted.

To partially make up for the firepower lost by the M1 incompatibility with the old drum magazines, newly designed stick magazines, introduced in 1942, now had a capacity of 30 rounds. One unique characteristic of both types of stick magazine is the inclusion of a vertical rail at the rear of the magazine body. Though this would not have been needed on the M1 versions, had they been designed with a magazine well, it had been a requirement on the old drum capable Thompsons, because of the interference that a magazine well would have caused to installation of the drum. Thus the newly designed stick magazines would fit the previous drum capable models, many of which were in use by U.S. forces at the time. It would also be possible to use the stock piles of existing Thompson sticks, without modification in the new M1 models. This course was not followed with the introduction of the Thompson's successor, the M-3 "Grease Gun". The M-3 had a magazine well, and used single track magazines, which were much simpler, and easier to manufacture. The comparatively crude, and primitive M-3 never inspired the kind of admiration or cultishness that was lavished upon the Thompson.

The Thompson stick magazines are of the double column type, much like a modern high capacity pistol magazine; but they require no magazine well. Unlike most high capacity magazines, which are completely encased in their tight fitting magazine wells, those of the Thompson hang out in the open. They are held in place by a partially enclosed slot milled into the gun's receiver. The rail on the back of the magazine fits up this slot, and guides the magazine into place. A catch within the slot engages a hole in the magazine's guide rail, locking it in place. So the catch is on the back of the magazine, rather than the more familiar side, as in most pistol and assault rifle magazines. These magazines are also substantial, and do not have the throw away design of many contemporary designs.

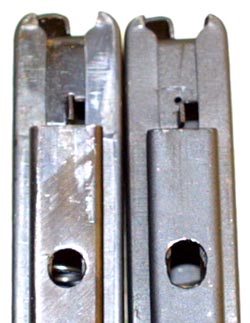

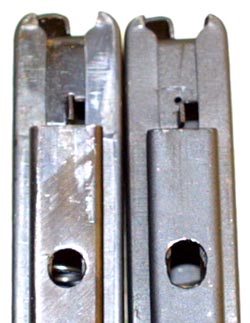

I mentioned above that efforts were made

to retain compatibility between different magazine styles, and the different

Thompson firearms; but this was not always perfect. The modern Thompson

expects to find a hole for the magazine catch an inch below the top

of the vertical rail at the rear of the magazine. All modern magazines

are so constructed, but there are some surplus mags which differ slightly.

These magazines have the hole just a fraction of an inch too low, and

will not lock properly into the firearm. This was done intentionally,

by the military, so that the magazines could be fitted to particular runs

of rifles, some of which might vary due to wartime production economies.

The solution is simply to slightly raise, and enlarge the hole with a file.

In many cases, you will find that this has already been done, either by

the Army, a factory refurbishment, or a previous owner. If you look at the

photo of my stick magazine, above, you will note that the hole for the catch

is somewhat oval. Compare this to the photo at left, of an unmodified, WWII

surplus, magazine, next to a modified magazine, and you will note that the

hole for the catch is round. If you should purchase a surplus stick magazine,

which was never issued, and still in the wrap, you may have to perform this

little task yourself. The best tool for this is a plain old half round file,

though a moto tool might also be used, if proper care is exercised. Using

a file, you should check the fit of the magazine after every few strokes.

It is very important not to take off too much metal, or the

I mentioned above that efforts were made

to retain compatibility between different magazine styles, and the different

Thompson firearms; but this was not always perfect. The modern Thompson

expects to find a hole for the magazine catch an inch below the top

of the vertical rail at the rear of the magazine. All modern magazines

are so constructed, but there are some surplus mags which differ slightly.

These magazines have the hole just a fraction of an inch too low, and

will not lock properly into the firearm. This was done intentionally,

by the military, so that the magazines could be fitted to particular runs

of rifles, some of which might vary due to wartime production economies.

The solution is simply to slightly raise, and enlarge the hole with a file.

In many cases, you will find that this has already been done, either by

the Army, a factory refurbishment, or a previous owner. If you look at the

photo of my stick magazine, above, you will note that the hole for the catch

is somewhat oval. Compare this to the photo at left, of an unmodified, WWII

surplus, magazine, next to a modified magazine, and you will note that the

hole for the catch is round. If you should purchase a surplus stick magazine,

which was never issued, and still in the wrap, you may have to perform this

little task yourself. The best tool for this is a plain old half round file,

though a moto tool might also be used, if proper care is exercised. Using

a file, you should check the fit of the magazine after every few strokes.

It is very important not to take off too much metal, or the magazine will be ruined, at least for your particular gun. You can

always take off a bit more metal, but you can not add it back on again,

if you take off too much. I want to emphasize the fact that these magazines

are not defective. Having to make this modification is normal, and the magazines

were made this way intentionally, so that the magazines could be fitted

to any run of Thompsons, made by any manufacturer. As a matter of fact,

if you have an older Thompson, this modification will not be needed, and

a modified magazine will not fit properly.

magazine will be ruined, at least for your particular gun. You can

always take off a bit more metal, but you can not add it back on again,

if you take off too much. I want to emphasize the fact that these magazines

are not defective. Having to make this modification is normal, and the magazines

were made this way intentionally, so that the magazines could be fitted

to any run of Thompsons, made by any manufacturer. As a matter of fact,

if you have an older Thompson, this modification will not be needed, and

a modified magazine will not fit properly.

During the clinton magazine ban, the stick magazines were in relatively good supply, and once the initial panic ebbed, they were available at reasonable prices. At the same time, drum magazines were nearly impossible to find, and once found, sold for nearly as much money as the, rather expensive, guns did themselves. The stick magazines are now easily available, very cheap, and are legal in most places. For about $100, I bought a set of seven, shown to the right along side the original stick that came with the gun. All needed modification in order to fit in my gun. This is cheaper than most pistol magazines, and is probably a reflection of the fact that there are millions of sticks out there, made for war time M1 Thompsons, but not too many civilian owned models these days. The drums, too, are more readily available, though in all honesty, the introduction of the 30 round stick, for war use, makes the weight, complication, and expense of the drum a bit silly, and hard to justify. Still, along with my sticks, I have several drums. This is, after all, a Thompson, but more about that in the next section.

Installing the Thompson Drum

Though these guns are forever associated

with their drum magazines, it has always been far more common to see

a Thompson loaded with a twenty or thirty round stick magazine. This

was particularly true after the introduction of the M1 models, during

the Second World War. These newly designed models, stripped down for

ease of manufacture, were not capable of taking the drum magazines. This

was due, in large part, to the cost of the drum magazines, but weight,

and the relative fragility of the complicated winding mechanisms were

also factors. Millions of M1 Thompsons were manufactured, while the drum

capable 1921, and 1928 models numbered only in the thousands.

Though these guns are forever associated

with their drum magazines, it has always been far more common to see

a Thompson loaded with a twenty or thirty round stick magazine. This

was particularly true after the introduction of the M1 models, during

the Second World War. These newly designed models, stripped down for

ease of manufacture, were not capable of taking the drum magazines. This

was due, in large part, to the cost of the drum magazines, but weight,

and the relative fragility of the complicated winding mechanisms were

also factors. Millions of M1 Thompsons were manufactured, while the drum

capable 1921, and 1928 models numbered only in the thousands.The drums could also be quite a chore to load, and maintain, and were fairly difficult to install, particularly in the heat of battle. If the small "Third Hand" used to install the drums was lost, installation could be next to impossible. Drums were also susceptible to denting, overwinding (or lack of winding), and could make the already heavy guns really clumsy to handle.

The original Thompson stick magazines had a capacity of 20 rounds; for extended firing, the drum magazine was used. When the military redesigned the Thompson for the Second World War, the drums were not considered to be practical. It was also noted that several additional manufacturing steps were required, to make the guns capable of accepting them. These steps were eliminated from the M1 versions, which served to simplify manufacturing, thus the cut out, and guide slots needed for the drums were deleted from the design. The external magazine latch was also deleted.

To partially make up for the firepower lost by the M1 incompatibility with the old drum magazines, newly designed stick magazines, introduced in 1942, now had a capacity of 30 rounds. One unique characteristic of both types of stick magazine is the inclusion of a vertical rail at the rear of the magazine body. Though this would not have been needed on the M1 versions, had they been designed with a magazine well, it had been a requirement on the old drum capable Thompsons, because of the interference that a magazine well would have caused to installation of the drum. Thus the newly designed stick magazines would fit the previous drum capable models, many of which were in use by U.S. forces at the time. It would also be possible to use the stock piles of existing Thompson sticks, without modification in the new M1 models. This course was not followed with the introduction of the Thompson's successor, the M-3 "Grease Gun". The M-3 had a magazine well, and used single track magazines, which were much simpler, and easier to manufacture. The comparatively crude, and primitive M-3 never inspired the kind of admiration or cultishness that was lavished upon the Thompson.

The Thompson stick magazines are of the double column type, much like a modern high capacity pistol magazine; but they require no magazine well. Unlike most high capacity magazines, which are completely encased in their tight fitting magazine wells, those of the Thompson hang out in the open. They are held in place by a partially enclosed slot milled into the gun's receiver. The rail on the back of the magazine fits up this slot, and guides the magazine into place. A catch within the slot engages a hole in the magazine's guide rail, locking it in place. So the catch is on the back of the magazine, rather than the more familiar side, as in most pistol and assault rifle magazines. These magazines are also substantial, and do not have the throw away design of many contemporary designs.

I mentioned above that efforts were made

to retain compatibility between different magazine styles, and the different

Thompson firearms; but this was not always perfect. The modern Thompson

expects to find a hole for the magazine catch an inch below the top

of the vertical rail at the rear of the magazine. All modern magazines

are so constructed, but there are some surplus mags which differ slightly.

These magazines have the hole just a fraction of an inch too low, and

will not lock properly into the firearm. This was done intentionally,

by the military, so that the magazines could be fitted to particular runs

of rifles, some of which might vary due to wartime production economies.

The solution is simply to slightly raise, and enlarge the hole with a file.

In many cases, you will find that this has already been done, either by

the Army, a factory refurbishment, or a previous owner. If you look at the

photo of my stick magazine, above, you will note that the hole for the catch

is somewhat oval. Compare this to the photo at left, of an unmodified, WWII

surplus, magazine, next to a modified magazine, and you will note that the

hole for the catch is round. If you should purchase a surplus stick magazine,

which was never issued, and still in the wrap, you may have to perform this

little task yourself. The best tool for this is a plain old half round file,

though a moto tool might also be used, if proper care is exercised. Using

a file, you should check the fit of the magazine after every few strokes.

It is very important not to take off too much metal, or the

I mentioned above that efforts were made

to retain compatibility between different magazine styles, and the different

Thompson firearms; but this was not always perfect. The modern Thompson

expects to find a hole for the magazine catch an inch below the top

of the vertical rail at the rear of the magazine. All modern magazines

are so constructed, but there are some surplus mags which differ slightly.

These magazines have the hole just a fraction of an inch too low, and

will not lock properly into the firearm. This was done intentionally,

by the military, so that the magazines could be fitted to particular runs

of rifles, some of which might vary due to wartime production economies.

The solution is simply to slightly raise, and enlarge the hole with a file.

In many cases, you will find that this has already been done, either by

the Army, a factory refurbishment, or a previous owner. If you look at the

photo of my stick magazine, above, you will note that the hole for the catch

is somewhat oval. Compare this to the photo at left, of an unmodified, WWII

surplus, magazine, next to a modified magazine, and you will note that the

hole for the catch is round. If you should purchase a surplus stick magazine,

which was never issued, and still in the wrap, you may have to perform this

little task yourself. The best tool for this is a plain old half round file,

though a moto tool might also be used, if proper care is exercised. Using

a file, you should check the fit of the magazine after every few strokes.

It is very important not to take off too much metal, or theDuring the clinton magazine ban, the stick magazines were in relatively good supply, and once the initial panic ebbed, they were available at reasonable prices. At the same time, drum magazines were nearly impossible to find, and once found, sold for nearly as much money as the, rather expensive, guns did themselves. The stick magazines are now easily available, very cheap, and are legal in most places. For about $100, I bought a set of seven, shown to the right along side the original stick that came with the gun. All needed modification in order to fit in my gun. This is cheaper than most pistol magazines, and is probably a reflection of the fact that there are millions of sticks out there, made for war time M1 Thompsons, but not too many civilian owned models these days. The drums, too, are more readily available, though in all honesty, the introduction of the 30 round stick, for war use, makes the weight, complication, and expense of the drum a bit silly, and hard to justify. Still, along with my sticks, I have several drums. This is, after all, a Thompson, but more about that in the next section.

Installing the Thompson Drum

Loading, winding, and installing the drum in a Thompson, is actually a matter of some difficulty. This is very unlike the quick insertion of a stick magazine. Even more difficult is the removal of the Thompson drum. The drum may only be removed, and installed, with the bolt held back. This would seem easy enough, but the Thompson has no automatic hold open for it's bolt, and the spring powering it has considerable force. What is needed is a third hand to hold the bolt back, while one hand grasps the Thompson, and the other inserts the drum magazine. The "Third Hand" is what Thompson calls it's special tool for engaging the bolt hold back lever. With a little practice, installing a Thompson magazine can be reduced from a difficulty, to a mere annoyance. No wonder the Army determined that it was unsuitable to field use. Step by step instructions are below.

| Installing

a Thompson Drum Magazine. Imagine doing all of this out on a battle field, while you are being shot at, and holding an empty Thompson. |

|

| Insert the "Third Hand" key up the keyway,

while depressing the magazine release. The Third Hand will remain locked

in place, once you let go of the magazine release. You can leave it

in, the whole time the drum magazine remains in place A photo of the Third Hand is directly below:

|

|

| Pull the cocking lever all the way to

the rear, and push up on the "Third Hand". This will lock the bolt

back. The top of the Third Hand trips a lever which holds the bolt open.

Once the bolt is held open, the Third Hand may be removed, though it

is a better practice to leave it locked in place, to prevent loss. |

|

| With the bolt now held back, insert

the drum from the left side only. Inserting it from the right could

damage drum locking tabs, or your gun. You will need to insert the guide

rails of the magazine into the cut outs on the frame. It may help to

partially release the magazine catch. |

|

| Push it in until it snaps into place.

You are now ready to play Elliot Ness. |

|

| To remove the drum, you must insert

the "Third Hand" back up the keyway, if it is not already there, and

lock the bolt back, as during the initial installation. This is potentially

dangerous, if the drum is still loaded. Needless to say, the safety

needs to be on. The Third Hand fits up the same keyway that acts as

a guide for the stick magazine rail. Thus the Third hand can not remain

in the gun, if a stick magazine is to be inserted, though it can remain

in a gun with a drum installed, or with no magazine in place. |

|

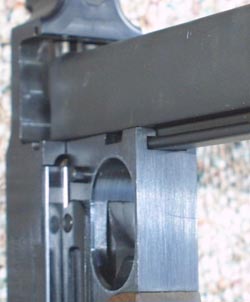

| Release the magazine catch, and slide

the drum out the left side of the receiver. Never push it to the right.

This photo shows why. If you look towards the lower left hand side

of the photo, you will see a pair of convex extensions stamped into the

metal plate affixed to the drum. These form a catch for the magazine

release. Note that they are on the left hand side of the drum. Should

you attempt to insert the magazine from the right side of the receiver,

you will find the receiver opening too narrow, and the catches, being

stamped into a sheet metal cover, will probably become deformed, and ruin

the magazine. This will also scratch up your gun. |

|

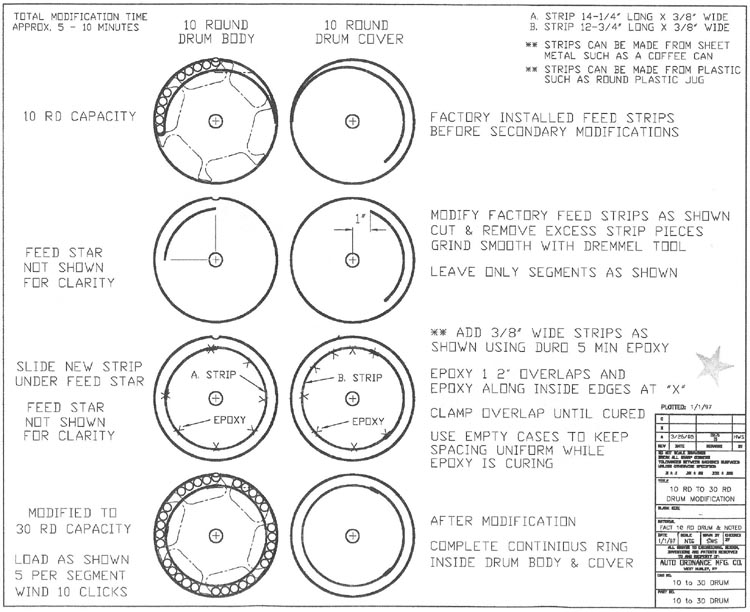

| Converting

the 10 round "X" magazine to increased capacity (coming) |

|

| It is possible, with

only a small amount of skill, and simple tools, to convert the dreaded

10 round "X" style magazine to hold either 30 rounds, or the full fifty.

Doing so, a year or so ago, during the ban, would have been a quick ticket

to prison. It is now perfectly legal, unless you live in one of the backward

states listed below. A thirty round conversion is simply a matter of removing the guide tracks from the top, and bottom of the magazine body, and fitting a specially made ring to the spider. A fifty round conversion is a bit more involved, requiring, besides the removal of the old tracks, their replacement with a new set. I will post photos, and descriptions of my experiences as I complete the project. Another method is show below. |

|

It is also possible to convert the drum to 30 round capacity, by modifying

the feed tracks. The instructions to the left are circulating right

now, and were drawn up by Auto Ordnance, in response to the large number of

ten round drums in circulation. Now that the ban has ended, there is no reason

for Americans to be saddled by the limitations of the ten round drum.

It is also possible to convert the drum to 30 round capacity, by modifying

the feed tracks. The instructions to the left are circulating right

now, and were drawn up by Auto Ordnance, in response to the large number of

ten round drums in circulation. Now that the ban has ended, there is no reason

for Americans to be saddled by the limitations of the ten round drum.

Unfortuantly, several states have quietly succeded from the union, and are no longer under the Constitution. Along with their fellow socialists in canada, the rulers of these rogue states have forbidden their subjects to own magazines which hold over ten rounds. California, Hawaii, New Jersey and New York all have bans against magazines holding over 10 rounds, and Massachusetts requires a special license. Maryland bans magazines which hold over 20 rounds. In addition to some state restrictions, some localities (like chicago), may have bans of their own. The prudent gun owner will want to check the law before undertalking such a project. |

|

| Modifying

the New Style Thompson Magazine Catch. |

|

| For reasons beyond comprehension,

the magazine catch on the newer Thompson models has been changed. This imposes

the requirement that surplus military stick magazines be modified

before they will fit the newer civilian guns. As an alternative, the magazine

catch itself might be modified, though I do not recommend this approach.

I am far more comfortable with taking a chance on hacking up a $20 magazine,

then on grinding away at a $1000 firearm. Performing the modification will require, in addition to courage, a Dremel tool, or a file, and a dowel. The magazine catch must first be removed from the firearm. It is then reshaped, and reinstalled. There are two problems with attempting this modification, about which I feel obligated to warn the home gunsmith. The first is that taking off too much metal will ruin the magazine catch. The second is that the purchase of a new magazine catch is not a guaranteed fail safe. A new catch may need some hand fitting. Probably the best procedure to follow, is to remove the original catch, setting it aside, and purchase a new catch, then attempting the modifications on the new catch, thus retaining the original in case of mishap. In truth, it is not the catch, but the actual frame itself that has been changed. In order to make it more difficult for the intrepid home gunsmith to install full auto parts for a full auto conversion. The change in frame dimension means that the standard magazine catch is about 1/10 of an inch too high, for the standard stick magazine. I have included the instructions for the modification below; but will probably not attempt it myself. The instructions below are for reference purposes only, and I do not recommend that you perform this modification. If any one has attempted this procedure, either with success, or without, I would appreciate hearing about it. |

|

The magazine catch must be modified by lowering the lip that engages the magazine .100" while maintaining the original contours and shape. Make certain that the firearm is unloaded, place the safety in the fire position and squeeze the trigger. Using a dowel or other object that will not mar the finish of the frame push up on the pivot plate finger that holds the safety lever, push the safety out. After you have removed the safety, move the pivot plate so the ends of the pins are flush with the side of the trigger frame. Pivot the magazine catch out far enough to clear the magazine engaging protrusion from the hole in the trigger guard. Push on the pin part of the mag catch on the far side while pulling the catch out of the hole. Once the magazine engaging protrusion has cleared the side of the trigger guard, carefully allow the catch to rotate and unwind the spring. Remove the catch from the trigger housing . (Assemble in reverse.) When re shaping the magazine catch, you must duplicate all the contours and angles when lowering the engaging surface. Removing .100" will allow use of unmodified GI magazines. Be careful not to remove too much metal. You may have to re fit and test several times to achieve the optimal shape. |

|

| Thompson Links |

|||

| Mike's

machine guns |

About the M1927 |

The Tommy Gun Page |

Auto Ordnance |

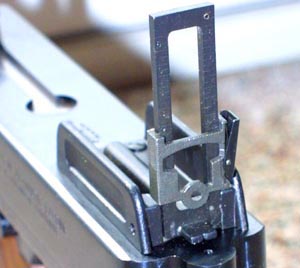

An adjustable leaf sight, just like on the original, which

folds down to become a standard notch sight. The leaf sight itself

is a peep sight which can be adjusted up and down a sort of a ladder.

The photo to the right shows the delicate sight folded down out of harms

way, while the photo at left shows it raised, for use at longer distances.

An adjustable leaf sight, just like on the original, which

folds down to become a standard notch sight. The leaf sight itself

is a peep sight which can be adjusted up and down a sort of a ladder.

The photo to the right shows the delicate sight folded down out of harms

way, while the photo at left shows it raised, for use at longer distances.